Support Us

Donations will be tax deductible

CEO of KORE Power, Lindsay Gorril, discusses renewable and electrical energy storage systems and technology.

On this episode, you will learn the following:

KORE Power has been around for three years, and has been in communication with global companies for about a year. The main goal is to become the leading developer of high-density, high-voltage energy storage solutions for global utility, industrial, and mission-critical markets.

As a cell manufacturer, the team at KORE Power produces lithium-ion cells and places them into modules which can then be placed in small energy storage platforms or used in massive peaker plants.

In essence, these batteries store any excess or what would otherwise be wasted energy so that it can be used at times of low energy production or peak usage times. In turn, this not only makes solar grids and renewables more efficient, but also limits the amount of time the peaker plants are being run, which reduces greenhouse gasses and lowers the environmental impact.

Gorril discusses how the coronavirus pandemic has affected the supply and demand for energy, and how it has shed light on the need for and usefulness of more energy storage to alleviate certain challenges.

He also explains why cost has historically been one of the greatest constraints on the technology now being developed by KORE Power, a recycling plan for the batteries they produce, how KORE’s technology can be delivered to and used in remote locations where power lines are not connected to large areas or by FEMA during global disasters, the three main parts of a battery and the technology behind the development of such high-density and high-voltage systems, and more.

Tune in and learn more at https://korepower.com/.

Richard Jacobs: Hello, this is Richard Jacobs with the Finding Genius podcast. My guest today is Lindsay Gorril. He’s the CEO of KORE Power. We’re going to be talking about the battery energy storage. KORE is the leading developer of these high density, high voltage energy storage solutions for global utilities and industrial and what they call mission critical markets. So Lindsay, thanks for coming.

Lindsay Gorril: Thanks for inviting me, Richard.

Richard Jacobs: Yeah, tell me how long have you been at this a battery creation? An energy storage game. And what is KORE focus on right now?

Lindsay Gorril: Sure. KORE Power has been around for three years, but we’ve only basically been talking to the global community for one year, but the company’s been around three years. And our main focus is to become the leading developer of high density, high voltage energy storage solutions for global utility. So this is just from small projects, which are like 500 kilowatt hours to massive peaker plants, which are one Gill gigawatt hour.

Richard Jacobs: What does it look like? What is your solution? Is it just like a big pile of batteries with cables connected to them and they act as a storage for a power utility or like what’s the functionality of what you make?

Lindsay Gorril: Sure. So we’re a cell manufacturer, there’s only a handful of cell manufacturers. We actually produce our own cells, which are lithium ion cells. And then we put those cells into a module. And the module is, is basically a couple of inches high by, you know, eight, 10, 12 inches long and 17 inches deep and they fit into a what looks like a server rack. So what you do then, it’s highly scalable. So if someone wants a small energy storage platform, they could put our modules in there. Like for example, EV charging stations. A lot of the EV charges that were built originally didn’t have storage next to them, but now they’re all being built with storage. Obviously it makes it more efficient and they can use it charging more cars, et cetera. And those are smaller things. And then if someone’s building a massive peaker plant, which is say a gigawatt hour, they would basically just add on a whole bunch of our rocks. And these look like a simple, they look like a server rack. That’s about seven feet high.

Richard Jacobs: Okay. So for any application, the point is that you’ll store where the excess energy created and then when it’s needed, maybe at nights or at times when there’s low energy production, your batteries are a reserve for that function.

Lindsay Gorril: Exactly. I think one of the best examples is California. There’s a lot of articles going on in California now that, you know, California has spent billions of dollars on solar and wind, mainly solar, but the energy costs per kilowatt hour for the user has gone up. And really the reason for that is if you take a solar, so solar creates energy while the sun’s up, but a lot of the part of the day when the sun’s up, the, the grid is not being used obviously totally. So what happens is you have a middle day energy being produced that is basically being wasted. So if you put a storage next to it, the energy being created by the solar panel, instead of turn it off the solar panel, you just keep it going and it fills up the battery. And then at night when people go home from school or from work or whatever, say between 4:30 and 7:30, when the peak happens, a large utility instead of turning on their coal fired or the gas fired peaker plant, they can just consume the energy out of the batteries. And then at night you can do it again. You start with the batteries again at night when there is no one’s using the energy is being produced by the grid. And then during the morning, same thing, instead of turning these peaker plants on, which are basically the emit greenhouse gases, you can just turn the battery on. So what it does, it does two things. It makes the grid and the renewables much more efficient but also reduces your emissions greatly because you don’t have to turn these peaker plants on. And the speaker pants are big polluters.

Richard Jacobs: We’re talking right now on the time of the coronavirus. So I would think there may be all of a sudden now a huge demand for your batteries because you know so many people are in home. Energy use during the day now is probably, I don’t know. I mean I’m afraid to even wonder what 10 X what it used to be. So what’s going to happen in this environment and how are you guys going to play a role?

Lindsay Gorril: Well I think what we’re finding the worst is seeing actually the demand going up. So it’s kind of a weird situation because you have the big producers of lithium-ion batteries. All the plants are either in China or South Korea and both of them had massive shut-downs obviously for two to going on three months and now there are backup going again. So you have supply chain that was pretty well sold out in January for the whole 2020 but now you’ve got two, three months’ supply has disappeared. So, and now the demand is starting to move back up again because of what’s going on. And we’re the only new production of lithium ion batteries in the world in 2020. So we’re only new production coming online, which our plant comes online full speed and end of May we’re also two months behind because of what’s going on. But yeah we see the demand and we also see what’s happened with the coronavirus. It’s kind of changed the optics of that there should be more storage and we’re finding more of that and now that storage is economic viable, which is obviously the most important thing. People are now saying, Hey, if we had more storage in these places, we’d have less issues. So I think, yeah, this is kind of an eye-opener to world on what are the things that we need to put in place to alleviate any type of future things like this. And storage is one of the big ones.

Richard Jacobs: So what are some of the constraints on what you do? Is heat, the big problem? Is long-term storage a problem, you know, like how long can you store energy if needed? What are some of the hold backs?

Lindsay Gorril: Well I think the main hold back in the past, which is just the cost. So you go back five years ago, your cost per kilowatt for storage. So if you’re going to store a kilowatt hour of energy, it’s like $1,200 now it’s no closer to $300. People always ask, well why do they put storage when they built the solar panels and solar farms and the wind farms, six years ago, 10 years ago, five years ago. Well the problem was with storage was too expensive, you just couldn’t do it. But now the price per kilowatt hour has gone down so much that it’s become an economic viable to put in storage. And this isn’t just renewable and storage, this is storage stand alone to where you would actually just build a storage that takes energy off the grid at non-peak times. And then reuses it into grid high peak times again to reduce the need for these basically fossil fuel or coal fired peaker plants.

Richard Jacobs: So how long can you store energy? Like is there a slow leakage of it or is it barely leak at all? Can you store it for a very long time?

Lindsay Gorril: Yeah, you could store for a long time. Obviously every single battery in the world has some sort of reduction of a charge over a period of time if it’s not used. But today’s technology is so minor. Like for example, if you had energy storage at your home, say, and you’re out on the wilderness. So we do a lot of work on islands, in places like mid Africa, West Africa that have big grid issues. Well, you would charge the battery with solar or wind mainly solar in those areas. And then if you need the extra energy for five, six, seven, eight days a month, it would still be fine. I mean the technology has changed quite a bit and then you’d have the batteries themselves, the batteries themselves are now usable for more than 10 to 15 years already. And on top of that, even though we’re new we did a MOU with a company called Renewance a number of months ago. So before we even started production, we started working with a company on recycling. So we’re already looking ahead of time looking at 10 years out when our batteries are now being half or 15 years out when they want to reuse them, recycle them, like do with lead acid batteries, we’re going to have a way to do that effectively.

Richard Jacobs: So are you going to be doing a lot of retrofitting on installations that haven’t had backup but now could have it?

Lindsay Gorril: Correct. Yeah, I think what you’re finding now is people are going back to retrofit either EV charging stations, solar farms, wind farms. On top of that I would say almost a hundred percent of the wind farms and solar farms are now being looked at and being built, have storage. But yeah, the retrofitting is one of the things that we don’t do that specifically in our company. We supply the product. We used to buy the product to the EPC, whoever is actually doing that.

Richard Jacobs: The thing also until now, this has been partly responsible for the, the lack of prevalence of solar and wind. Now that if I wanted to put solar in my commercial building or something or in my city and I didn’t have backup I’d be facing X amount of cost. But now with backup and storage, it seems like it may be economically feasible for solar and wind to delivery because of this.

Lindsay Gorril: For sure. I mean you what we’re doing right now, I’ll give you an example. Call it an apartment building, call it a small village in West Africa. Call it an Island in the Caribbean and they’re all standalone items and then these other areas, they’re run amazing mainly on diesel or because their grid isn’t good. So you roll into like your apartment building, same thing there. Solar is only good. So not only creates energy when the sun’s up, if you don’t have storage, you can’t run it 24 hours. You can’t run your apartment building or your house 24 hours a day. It’s impossible because the energy density of the batteries, they’ve got so much greater and the cost per kilowatts come down then you actually can set something up, whether it’s a residential subdivision, whether it’s apartment, whether it’s an Island, small little village where there’s a mining company somewhere in the middle of nowhere, you can now set up a system where mainly solar and storage can run your facility, your apartment, your company, 24/7. You’ll always be tied to the grid just in case something happens. You need some grid thing, but you should be able to run the majority of your energy from renewables and you couldn’t do that in the past. That was impossible because the wind and the sun only increase energy when it’s there. And if you don’t create it when you need it, you lose it. So yeah, that’s exactly right.

Richard Jacobs: Is it at the point where you could create you know, imagine, let’s say it’s some remote areas that you have maybe a central power plant, but they just haven’t able to get power lines out to a large part of the area. You drive in a truck full of these cells, charge them up at the power plant and then drive them out to a site and they sit there for a week or a month powering nearby machinery. Is that possible?

Lindsay Gorril: A hundred percent possible. So you have a system where you put it on almost like a container, right? You put it on the back of a truck. You could charge it from a substation somewhere. You could charge it, drive it out there. You might even have two of them under our drives out there. It sets in place. Everything’s discharged off at the run, whatever you’re running, and the other one comes back and gets charged. So you could basically run it. So this place that doesn’t have a connection at a time could still function fully. Correct. It’s almost like someone like FEMA. Let’s look at the natural disasters. So if you look at natural disaster, what happened in new Orleans and some of the fires in California recently, if FEMA had a bunch of containers of these batteries, they could drive around truck, charge it somewhere else, drive it down, hook it up to a grid to wherever that may be, and to provide power to people and now if you think about it, I mean, just to continue. So if you think of a container, a container would hold about five megawatt hours of batteries approximately. And that’s today’s scenario. With the old days, there’d be one. Well, you could charge and run thousands of households for a number of days, so you could have a container going down, run the households for two or three days and before it runs out, another container comes down. So it’s good just for what you said, but also in national disasters globally that you can set these things up.

Richard Jacobs: So what kind of power can be produced by the batteries? 120, 240. There’s certain grades of power that can and can’t be produced.?

Lindsay Gorril: Any grade, depending on what your inverter is like. So you can’t just pick the battery, plug it into the, you have to have an inverter in between it. Usually the container will come with a small transformer and an inverter. So you basically have it packaged up to whatever type of power you need. But it can be any type of power.

Richard Jacobs: Oh, depending on the type of power. Does that deplete the batteries a lot faster?

Lindsay Gorril: Yeah. It’s really more about how much you’re drawing, how much you need the battery so that is less of an issue. If you come down and you want the whole battery in one hour, or do you need over four hours or what do you need the battery for? So depending on what your demand is really what draws a battery down. Whatever the power is, has really almost no effect on drawdown.

Richard Jacobs: Gotcha. So what’s made an economical? Maybe you could talk a little bit about the technology, like how has it become dense enough and efficient enough that it’s now economical?

Lindsay Gorril: So I think what’s interesting is people always talk about lithium ion batteries, right? And when in reality, it’s not a lithium ion battery, it was a way back. But now you’ve got a number of other different things. So when you look at a battery, you have sort of three parts of the battery. You have what’s called the anode and cathode and one of it’s usually graphite related. The other one can be either NMC, which is nickel, manganese, cobalt. It could be LFP, it could be LTT. There’s a couple of different other types. But one of the things people forget about is in the middle of it all is what’s called the electrolyte. And the electrolyte is with a lot of lithium is, and it is the thing that makes the molecules move back and forth. So when you charge and discharge molecules are going from back and forth, positive, negative, back and forth as you charge and discharge, the better the electrolyte, the less the molecules, how do you want to say degrade? So if you have a hundred human molecule that’s perfectly round and you charge and discharge now has a little chip on of it. So over time it can hold less of a charge. That’s what degradation does. So the first thing that’s happened is these electrolytes are becoming so good that when the molecule goes over to charge and discharge, it doesn’t degrade. It takes a long time for degrade. So now you have a battery that last and maybe the ones that came out 10 years ago lasted five years or now lasted 15 years. So that’s the first thing. The second thing is the chemistry. So, I can talk about the normal chemistry people talk about NMC, which is nickel, manganese, cobalt, but there’s a lot of other things in there besides that. And there’s been a lot of work on first you’ve got the electrolyte, which is basically the longevity. And then you’ve got the chemistry that says how much energy can I pack into a cubic foot? And a lot of work’s been done on that. So like my best example is if you look at a container or set on a back of a truck. Five years ago, it could hold one megawatt hour of energy. Today it could hold almost five. And it all relates to the chemistry of the battery and its ability to hold the energy more energy in a small area, I guess its the best way to explain it to your listeners.

Richard Jacobs: Right. The energy density. So what’s your goals for the next 12 months? Just get your system into a lot more places and if so, like preferentially, what kind of places do you see really need your energy storage solutions?

Lindsay Gorril: Yeah, so I think we have two goals in the next 12 months. The first goal is our new production facility which is two gigawatt hours, which will go to six gigawatt hours by the middle of next year. Its in production. We’re shipping next month for the global market and really getting our product out into the market. So it can be integrated, used and then obviously approved. So, we have got all the certifications to get that stuff done. Now we’ve got to get to the marketplace and that’ll take us a few months to get that done. So by August, September, we have a number of our Mark ones integrated into large solar storage. EV charging station storage. It could be micro grid storage, often Africa, some places in India, all that be done between now and September to prove our product and prove the integration. On top of that, by the September we’ll have selected the site for our US manufacturing plant. So our first manufacturing plant is in China and our second manufacturing plant will be in the United States and we will be announcing the state and the site in September.

Richard Jacobs: Okay. Is there any new technology that’s coming that’s really going to make a step function improvement in what you already have?

Lindsay Gorril: I think we work on it all the time. We have a 500 engineers in our facility in China and so we work through in, what’s interesting is we are also a critical supplier. So my background was a critical minerals and mining and how I met my partner was there a chemical company and they develop all the streams for flooring, silica and lithium. And so as a chemical company we spent a lot of time on the chemistry side of it. And then on the engineering side, on the design of the packaging, et cetera. So our chemistry changes all the time. I’ll give you an example, six months ago we have what we called a six, two, two, so six parts nickel, two parts manganese, two parts cobalt. We’ve moved that to six and a half parts nickel, two parts manganese and one and a half parts cobalt. What that does is it adds density and it lowers the cost. So that’s just as one part of the battery. So we are looking at stuff for it today that we think will be our evolution a year from now. So we are continuously spending around $30 million a year just on that.

Richard Jacobs: Do you think that this is going to again inspire a big surge of renewable energy setups for cities or villages for commercial buildings, et cetera. Again, I don’t see a lot of solar when I go to various cities, for instance, in the US like, do you think this will cause a tipping point where there’s going to be a huge predominance of it, the near future? Because now we’ve got some great storage capacity?

Lindsay Gorril: I think so because now those become efficient because before even having a solar on in a city, in some respects, the cost of the solar and what you can get out of it doesn’t make economic sense. About most of the stuff that was built in the past and renewables is all done with subsidies, whether it’s the United States or Canada or Italy or wherever, India, it’s all been done mainly with subsidies in some respects. And what’s good about the storage side of it, you now can come out of the economic viable, you can do it without in some respects, without some subsidies, which is what you want. Once you get to that point, then everybody does it. And I think we’re getting close to that.

Richard Jacobs: Okay. Is there any particular type of power generation that’s most amenable to what you do?

Lindsay Gorril: No. We can be tied to anything. So the thing about an EV charging station, which is probably everybody knows what those are. So an EV charging station which could be the tied to the grid or tied to solar and next to it is a battery. So what happens is that whatever the sources and it’s the best time for sources to be utilized and you charge the battery. So it can be any source works.

Richard Jacobs: Okay. Very good. So what’s the best way for people to find out more about your applications and see if they want to get the storage component going with you?

Lindsay Gorril: Sure. Just go to our website, , which is www.korepower.com and we’ve got all the information on the website, our products and also all our contacts globally.

Richard Jacobs: Okay, well, very good. Well, Lindsay, I think it’s going to be a big game changer because again, I’d like to see renewables everywhere and if this can help them do that, I mean that’s maybe one of the greatest things that this accomplishes, at least in my mind. So I’m glad you came and I appreciate you talking about this.

Lindsay Gorril: Oh, I thank you for the invite, Richard. Really appreciate it.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

In this conversation, we sit down with a member of Doomberg to discuss the mindset of continuous improvement and other thought-provoking ideas that are important for us all… Read More

In this episode, we discuss teenage social anxiety with Kyle Mitchell, a Tedx Speaker, author, and the founder of Social Anxiety Kyle. With a passion for solving mental… Read More

In this episode, we are joined by Matthew Moody, the President of Mental Health America of Arizona and a licensed counselor in Arizona. He has a Bachelor’s degree… Read More

Do pre and probiotics have healing and preventive powers? In an age of pharmaceutical solutions, finding sustainable and holistic health practices is critical. How can we leverage gut… Read More

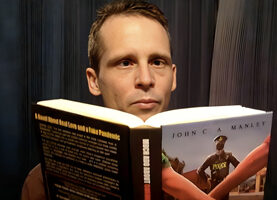

John C. A. Manley joins the podcast once again to discuss his daily email newsletter, Blazing Pine Cone Posts, and his work as a writer of fiction, freedom,… Read More

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get The Latest Finding Genius Podcast News Delivered To Your Inbox