Support Us

Donations will be tax deductible

Scott Carver is a lecturer in wildlife ecology at the University of Tasmania who joins the show to discuss his research in the field of ecology and infectious diseases in wildlife, domestic animals, and humans.

In this episode, you will learn:

Carver has a long-standing interest in connecting an understanding of ecosystem health with the health of animals and humans. Over the course of his education and career, he’s conducted research on mosquito-borne diseases, viral transmission in bobcats, mountain lions, and domestic cats, and even chlamydia in koalas.

These days, Carver’s research revolves largely around sarcoptic mange in wombats. It’s a disease that affects over 100 different species, including humans (when it affects humans, it is called scabies), and creates both conservation and animal wellness issues. His research is geared around trying to find disease management solutions for this disease in wombats and other affected species.

Carver explains that wombats suffer from a version of mange called crusted mange, which is a particularly severe form of the disease that ultimately results in death. He discusses the ways in which the low metabolic rate of wombats could contribute to the severity of sarcoptic mange, why he has chosen to focus on the wombat as a research subject for better understanding the disease, and much more.

Press play for the full conversation and check out https://www.utas.edu.au/profiles/staff/zoology/scott-carver to learn more about Carver’s research.

Available on Apple Podcasts: apple.co/2Os0myK

Richard Jacobs: Hello, this is Richard Jacobs with the Finding Genius podcast. I have Scott Carver. He is a lecturer in wildlife ecology at the University of Tasmania and he specializes in the ecology and epidemiology of infectious diseases in herds of wildlife and domestic animals and how it affects humans. So, Scott, thanks for coming. How are you doing?

Scott Carver: Thank you, it’s great to be here.

Richard Jacobs: Yeah, so what got you interested in looking at ecology and epidemiology of wildlife animals and how they affect people?

Scott Carver: I guess, for me, it started probably back when I was doing my undergraduate degree. I’ve always headed towards working with animals and animal conservation and during some of our Masters’ studies, I really got interested in these ideas around sort of connecting ecosystem health with the health of animals and also the health of humans as well and that led me into a Ph.D. working on mosquito-borne disease ecology and then ultimately moving on to other sorts of wildlife disease systems in different parts of the world.

Richard Jacobs: So, I was thinking that was focused on certain animals or certain parts of ecology, like what is your focus? Is its habitats? Is it a disease? What animals?

Scott Carver: It’s really a disease and I have a few systems that I generally work with now, now that I have stables, a lot of my research now focuses on wombats that are infected by this disease called sarcoptic mange but also do and have done a lot of work in the US working on how viral transmission of a variety of different viruses in bobcats and mountain lions and domestic cats and then I still tinker around the edges with mosquito-borne disease ecology in Australia where we found a virus called the Ross River virus which cycles between marsupials and humans and then there is a few other things like Koalas that get impacted by a Chlamydial disease. So, we are doing lots of different things and that’s just what I work on now. I’ve also worked on Hantaviruses in the US which are spread by a small mouse and other things as well.

Richard Jacobs: In Koalas, I’ve heard that there is a virus that is endogenizing, it’s becoming part of their DNA and it’s changing over the entire population. Am I right about that? Is that what’s happening or is it something different?

Scott Carver: No, that’s absolutely correct. There is a virus that is called Koala retrovirus and abbreviated, people call it KoRV and it seems to have been introduced to the sort of northern part of their range in Queensland and has been moving steadily south in Koalas and it has been doing it, it has been endogenizing into the genome. It is quite a complicated picture, so the people think that the virus has some health impact on the Koalas but it might be down to particular kinds of strains and there is lots of threats to Koalas like Hepatitis structure and there is also chlamydial disease and interactions with dogs and things like that. So, it’s quite a complex picture but that is certainly one of their mentioned diseases of interest.

Richard Jacobs: what is it doing to them? Is it killing them or is it just changing them in some unknown way?

Scott Carver: With it being a retrovirus, probably its major effect is through influencing the immune system. So, it’s still fairly unclear to be completely honest. But I think that sort of the greatest understanding is that it has some effects in terms of still compromising their immune responses and making them more susceptible to other forms of health risks and things like that. So, there is still much to be learned there. It’s an interesting disease that has not been entirely well understood yet.

Richard Jacobs: So, from where you are right now, are you looking at. I mean if it has to, has your attention been forced to look at local animals. Local ecology because of the coronavirus, the shutdowns, and the localization of everything, or what’s your work right now at this moment?

Scott Carver: Yes, that’s a very good point. Right at the moment, and really for the last few years, I’ve been headed with a growing focus on wombats which these wonderful Australian marsupials that live down burrows and come out and feed at night time and they spend a lot of time sleeping quite like koalas as well. They get really smashed by this disease called sarcoptic mange which was introduced to Australia by European settlers and their domestic animals a couple of hundred years ago. So, it sometimes is a conservation issue in Australia and it certainly causes population declines but more often, it’s kind of an animal welfare issue.

So, the populations can sustain the disease but the suffering added is quite horrendous to wombats and so a lot of my research these days is geared around trying to find disease management solutions to wombats and other animals that have this disease. It impacts over 100 species of mammals globally including humans which is a fairly complicated business but I think we’ve got some real chances to really make some positive gains for these animals.

Richard Jacobs: What role do they play in the ecology? They look like hamster dogs. I guess if you mix the two together.

Scott Carver: Yeah, they certainly do. They weigh, on average a dog wombat weighs 20 kg which I guess is about 50 lbs. and they can move pretty quickly over short distances. So, I’ve certainly been outrun by wombats on many an occasion. In terms of the ecosystem, they are herbivores, they graze on grasses predominantly and they are kind of minor ecosystem engineers. So, they dig these burrows that they live in and they’ll dig a variety of other burrows, and lots of other animals utilize those burrows. There were some media when they had the big bush fires in Australia earlier this year of other animals utilizing wombat burrows and that’s actually quite common. There are other animals who use wombat burrows for shelter.

They also just turn over the topsoil quite often as well. So, often they eat grassroots and they’ve got these sort of bit powerful arms and claws on their forepaws that they can use just like tearing through the top few centimeters of soil and kind of eating grassroots to obtain carbohydrates.

Richard Jacobs: So, what do they prey upon? So, they just eat grasses and they make these holes, do they help fields turn over? Do they attack crops? In terms of humans and wombats, what’s the interaction there, and again, what eats them?

Scott Carver: Yes, good question. So, in terms of Tasmania, one of the animals that eats the wombats is the Tasmanian devil. So, it’s a native marsupial carnivore and on the Australian mainland, it’s mostly things like dingoes and wild dogs. There are not too many things that eat wombats and they’ve got quite good defenses. So, wombats, when they see a predator, they will run down a burrow and they’ll stand in the tunnel of the burrow and they have this hardened skin on their backside which is very difficult for an animal to bite that or to get around because wombats kind of basically block the hole like a plug to stop predators from eating them and they are quite well known for occasionally actually killing things like a fox or an animal that tries to get over the top of a burrow.

The wombats in the burrow have got very powerful legs, so they’ll stand up and they’ll actually squash the animal against the roof of the burrow and basically suffocate them by compressing their airway. So, it’s got some quite amazing defenses and I guess on an ecosystem level in terms of the impact that they have on other animals is definitely nutrient in either of the soil and providing shelters for other animals as well. Not deliberately providing shelters for other animals but because they dig a lot of burrows and other animals tend to use them as well.

Richard Jacobs: Okay. So, the disease that’s affecting them, what does it do to the wombats? Again, I don’t know, I would wonder sadly if it hardly gets any funding to study this because they are not directly affecting people. Sadly, they may not care or they may think other animals are priorities.

Scott Carver: Yeah, so in terms of interactions with the humans, wombats; most of their negative interactions is where they, in the farming rural properties and they go out onto pasture land and consume grass there which they don’t consume huge amounts but wombats are kind of like little bulldozers and they are really good at like pushing through and underneath fences which leads to other marsupials. So a lot of their conflict with humans comes in the agricultural areas through impacting the integrity of farming fences or sometimes even undermining them by digging burrows around them and probably another main threat with humans is that they are not very good with vehicles on the roadways. So wombats do occasionally get hit by a car which usually does a reasonable amount of damage both to the wombat and the car because they are really solid creatures.

Richard Jacobs: Okay, how much do they weigh?

Scott Carver: They weigh about 20 kgs. On average an adult wombat is about 50 lbs. But they can get up to close to 40 kgs at their biggest size. So, they are not too small.

Richard Jacobs: Are they at all similar to capybaras? I know those are like giant rodents but they seem I guess a little bit similar. I don’t know.

Scott Carver: Yeah, I mean morphologically they are pretty similar in size to a capybara, yeah.

Richard Jacobs: Other matters they are not similar at all, right?

Scott Carver: No, they are not social, in fact, they are anti-social. Wombats are kind of like grumpy solitary loners. I think the way I would describe them is as juveniles they stick with their mum very closely but as they turn into teenagers, they want nothing to do with each other. So, mostly you find one wombat lives down a burrow on its own and of course, they interact to mate with one another but otherwise, they don’t even seem to like each other. So, it’s quite entertaining. So, wombats are impacted by this disease called sarcoptic mange and it causes really quite severe sort of symptoms. So, humans can also get this disease. It’s called scabies when humans get it and so domestic dogs and pets are best known for that.

Wombats get what we call crusted mange or crusted scabies which is really a most severe form of the disease where they have what we would call a Type 4 inflammatory response or you might even call it an anti-inflammatory immune response to infection which means that the number of mites, so it’s mites that cause this disease, multiply into very large numbers on the wombat and their immune response basically results in their skin thickening and cracking with hair loss and usually they become thinner and thinner and ultimately die of opportunistic environmental bacterial infections. There is really a severe disease on these animals and they really go through a period of absolute severe suffering over a period of 2 to 3 months before they usually die from it.

I guess one of the things that makes it so publicly well-recognized things in Australia is that people see sick and suffering wombats because they tend to be more likely to come out during the day and you can see that they are visibly lost here and they are visibly sick. So, that certainly drives public attention and helps us justify our research on these animals.

Richard Jacobs: So, are you trying to figure out how to stop the mange or is there something unique physiologically about the wombats that by learning about that and studying them it’s going to translate to other animals or other conditions?

Scott Carver: It is very much so. So, on both fronts, wombats have very low metabolic rates and we think that may be one of the reasons why they suffer such a severe form of the disease, not 100% certain about that but that’s my working hypotheses and the disease impacts lots of different animals. So, just to name a few in North America, there are quite significant problems with a black bear in East and North America impacted by sarcoptic mange, wolves in the Yellowstone National Park, and other carnivores there. In Europe, it really impacts things like mountain Ibex and shamoires and other antelopes that get impacted over there and really foxes around the world. It’s well known to impact them as well. So, it’s got this huge host range across mammal species and so what we are trying to do with wombats is really figure out the ways that we can manage this disease and it is a treatable disease so you can apply treatment to wildlife for that and there is a whole bunch of logistics about trying to manage disease in a wildlife population because they usually aren’t very good patients.

They don’t really want to be captured and handled and have treatments administered to them. So there is a bunch of logistics but what we learn with wombats we can really apply to other animals around the world as well.

Richard Jacobs: You said they had a very low metabolic rate; well how does it affect these mites from the sarcoptic mange ability to, does that mean that their immune system is not very tuned or what’s the consequence of them having a slow metabolism?

Scott Carver: Yeah, that’s not well understood. So, koalas can also get sarcoptic mange and both of them suffer the most severe forms of the disease whereas carnivores who have high metabolic rates like dogs and foxes tend to suffer what we call ordinary mange, in most circumstances and so do humans and really in those animals, the only time they get crusted mange or crusted scabies is when they are immune-compromised whereas wombats and koalas tend to always get crusted mange as far as we can tell. So, we hypothesize that maybe the immune response is slower because they have these low metabolic rates and maybe it’s just not as well geared up for the kind of inflammatory immune responses. We are not 100% sure and we are trying to figure that out

Richard Jacobs: What’re the benefits of a low range? Do they live longer? Are they able to handle heat and cold better or worse? What are all the consequences of low versus high metabolism?

Scott Carver: Yeah, for wombats having a low metabolism means that they ecologically really are really able to sustain themselves during difficult environmental conditions because they live underground. Those underground conditions are relatively stable when they are sleeping down their burrows and then they will come out and they will feed. A healthy wombat will feed for 2 to 3 hours a day and having a low metabolic rate means that they can kind of sustain on less food for longer than other things like your kangaroos or other macropod marsupials. So, if you have difficult environmental conditions like it hasn’t rained in a while and there’s a lot of competition for food resources, wombats are a little bit better geared up to last longer during those periods of environmental stress than most other herbivores that they compete with.

Richard Jacobs: Okay, so are you trying to just defend them against this disease, or are you trying to understand animals like them such as koalas? What do you think would be a beneficial understanding that you could achieve by studying them and studying animals that are similar to them?

Scott Carver: So, here’s a few reasons why we are focusing on disease and disease control and one of them is because it’s an invasive pathogen that was introduced by Europeans, it was a twist really, and in many other places around the world. There is a question that is sort of incumbent on us to do something about this quite significant suffering that we’ve caused to native wildlife in their country. So, that’s certainly one of the reasons. Another reason is that there is already a lot of people from the general community in Australia who try to treat these diseases in wombats, who see these animals suffering and want to do something about it.

So, one of our other reasons is to provide some good science that can be used to guide the general community who are already trying to manage this disease but don’t have the same expertise in treating these animals as most scientists and veterinarians do. More generally, it does cause conservation and welfare issues in other places all around the world and some of those are quite significant and people are quite concerned about those in many locations and so by advancing our capacity for disease control in wombats, we can really take what we’ve learned in this system and apply it to other systems to help other people also manage this disease and there is certainly plenty of cases of that as well.

Richard Jacobs: Is there anything truly interesting or amazing about wombats that makes them completely unique?

Scott Carver: I think wombats are great. When I started working on them, I saw a need and that was a real justification for me to start working on them but I think like all researches, you sort of fall in love with your study animals more and more over time, and as you learn more new things about them. One of the reasons wombats are certainly interesting in the sense that they are these burrowing herbivores that sort of come out and feed at night time. One of the really unique traits is that they are the only mammals that I know of that produce these cube-shaped poos which is quite unique and they basically use them as a form of communication.

So wombats are quite anti-social generally and deposit little piles of cube-shaped poos next to prominent objects in their landscape. It might be a rock, it might be a log or a little rise and that sort of thing and they use it as a form of social communication through the sense of smell that is created by those and then people have always asked this question that how do wombats produce these cubes when all other feces that animals produce are going to be kind of more cylindrical and so recently, we have been doing some fun research to try and understand that and that is being quite recognized internationally. We are very fortunate to win a Nobel Prize that last year for our research into understanding how wombats produce cube-shaped scats.

Richard Jacobs: Literally like a cube?

Scott Carver: They are literally like a cube, not all of them but a very significant proportion of them are cube-shaped.

Richard Jacobs: Do they come out that way or are they shaping them somehow or nudging them or stacking them?

Scott Carver: That’s exactly been the question that we are trying to figure out. So, there’s always a wonderful hypothesis on how wombats produce cube-shaped feces and nobody has ever tested them. So, one of my favorite ones is they have a square-shaped anal sphincter and so they push their feces out through that and it then gets turned into a cube. That’s wrong. There are even some extremely colorful hypotheses that wombats would pat them into shape after they had deposited them.

Richard Jacobs: Well, if they are using them as signaling then maybe they are doing that. I mean if they use them as signaling why wouldn’t they shape that? Maybe that conveys some information.

Scott Carver: They are definitely not doing it by patting it into shape physically after they have done them. So, we’ve done a number of dissections of wombats and these are the ones that have been hit by vehicles or have been euthanized as veterinarians for other health-related reasons. So sometimes I bring them back to my lab and we dissect these animals and one of the things we discover early on is that they actually form into cubes inside the intestine which is otherwise a sort of soft tube and up to a meter from the anus, you get these scats that are turning into cubes. So, we‘ve been working with some really great physicists and engineers, who think about these problems in a different way than biologists and so working together has just been really fun and it looks like the answer is that it’s a combination of the drying of the feces inside their intestine, in the lower intestinal colon and there’s sort of the veering stretch properties around the circumference of the intestine which is what creates that cube shape.

Then they get deposited out by the wombat and the reason we think why they do it is because the cubes are less likely to roll away when they deposit them on an object but we still need to do some fun experiments to test that hypothesis too.

Richard Jacobs: Oh, you mean the cubes are more likely to stay in place so they can accomplish the signaling that they want?

Scott Carver: Yeah, we think so. We think it helps them stay aggregated together, it’s the hypothesis anyway, of course, nobody has done the research on it, possibly because the research is more fun rather than the plot.

Richard Jacobs: How complicated is the signaling that they do? They leave them and does the mere presence signal other wombats, stay away, this is my territory? What do you think is going on?

Scott Carver: I think they are not territorial animals. They don’t actually defend territory to exclude other animals, they have quite overlapping high ranges with lots of other wombats but I think it’s a form of like, and we don’t actually know, to be completely honest, we don’t know but wombats will certainly walk along with the high ranges and will visit other poo piles and sniff them. So, we think that that’s more of advertising of who is there in an area. It may also signal things like whether somebody is reproductively active or not as well. It’s definitely some form of social communication but the exact details of that are a good question.

Richard Jacobs: Interesting. Anything special when they are mating? I mean does the female do very different things from the male or is there anything interesting there?

Scott Carver: So, when the female is in heat, the male tends to spend a lot of time chasing her around in circles and biting at her and then, when they actually do mate, wombats, because they are quite heavy animals they end up both laying on their side almost like a T intersection to one another. So, they don’t mount each other like a dog would or something like that.

Richard Jacobs: Or like people.

Scott Carver: I guess another feature of wombats is quite unusual. I think many people are familiar with kangaroos have a pouch the young one sits in; wombats certainly have that but their pouch actually faces the other direction because they are on all fours all of the time and they dig burrows and the pouch opening is actually to their back end.

Richard Jacobs: Really?

Scott Carver: Yeah, it is and it makes sense because if you are digging soil and pushing it underneath you, you don’t want your pouch facing forward because you can start filling it up. So, as for joey, joey points out backward.

Richard Jacobs: Really? How do they reach around and get them when they are; that would really mean that they can’t help their joey very much, they would have to do it themselves. I mean if they are so fat they can barely mate, how would they ever reach around to put anything in the pouch or take anything out?

Scott Carver: So, they don’t really and it’s a very good point and kangaroos certainly lick their pouches clean but wombats don’t and the birth of marsupials is basically a non-event because they give birth to a joey that’s about the size of a jelly bean. So, birth is very different for marsupials relative to placental mammals that give birth to much larger individuals. So, marsupials give birth and the joey that crawls from the cloaca into the burrow and for wombats, it’s a very small distance to crawl into there and then attaches to the nipple inside of the pouch and then more or less, will just stay there and the wombat will go about its thing until the joey reaches a certain size and then it starts to come out of the pouch periodically to feed on grass and as it becomes larger, it becomes more and more independent of the pouch but still hangs around with its mother and a joey wombat will stay with its mother for one and a half to two years in general before it becomes solitary itself or independent.

Richard Jacobs: I guess, we haven’t been comparing the pouches then to the kangaroo’s pouch, how many can fit in there? How many offspring do the wombats have? If you do a pouch-to-pouch comparison, what are the differences or similarities there?

Scott Carver: I guess, the main difference is the direction that the pouch opens. Pouches are broadly similar between a kangaroo and a wombat. What else would I say are the differences there?

Richard Jacobs: Can they accommodate the same number of offspring?

Scott Carver: Generally, they both have one at a time. You almost never see marsupials with twins in the pouch.

Richard Jacobs: But I had heard that in the kangaroo pouch, for instance, you will have a very young joey but also an older one that will not hang out there the whole time but will return to it to feed at a various point or to hang out and then there may be a younger brother or sister that is there as well or is that not true?

Scott Carver: It is not very common. Basically kangaroos and wombats, they are more or less always pregnant but they’ll have an embryo that is paused essentially and so, if for some reason, they lose their joey or if their joey becomes independent. So, pretty much a kangaroo or a wombat almost always has a joey in the pouch at different ages. If they lose it then they will have another one in there in a few days’ time. There are some marsupials that have a lot more young. There are some marsupial carnivores like your quolls or your devils actually have a litter of young but your macropods and your wombats and your koalas just seem to have no time.

Richard Jacobs: How many animals have pouches? I don’t know if you mentioned the names of a few other ones that I am familiar with but the wombats do, kangaroos do, what other large marsupials have those?

Scott Carver: Pretty much all of them do. The pouches vary a little bit like in the devil where the pouches are quite small in terms of the quoll but I’m just trying to think through if I know of any marsupials that don’t have a pouch and I’m not sure I do, just off the top of my head

Richard Jacobs: Tasmanian devils, I actually don’t know a lot about them. They are in Tasmania. Actually, can you maybe talk about those for a few minutes? I don’t know anything about them but it’s just not real; growing up watching the cartoons from Looney Toons but why are they called devils? What do you know about them?

Scott Carver: So, Tasmanian Devils don’t spin around in circles like the cartoons but are about these kinds of like corgi sized marsupial carnivores that look like a little dog really. I mean they are all black and they have a couple of white stripes on them and they are not very big but they are the top predators in Tasmania and were formerly more; they formerly occurred historically on the Australian mainland as well but were probably pushed to extinction by the introduction of the dingo probably 5000 years ago. So, they are now restricted to just Tasmania and they are mostly scavengers but they can also be active predators as well and what else can I tell you? What else would you like to know about Tasmanian devils?

Richard Jacobs: Again, are they called devils because they are really strong predators, or is it because when they attack, they are really vicious? Why are they called devils?

Scott Carver: Yeah, that’s a good question. They were originally called; Tasmanian Devil is really their European name and they were called that because at night times they have a call that sounds very ghoulish and is kind of like a rasping kind of scream and if you don’t know what it is and you had just come to this foreign country, I imagine that’s quite scary and so that’s how they picked up this name, the devil because of the sound that they make but in reality, they are actually quite a small dog-sized marsupial carnivore that is otherwise quite secretive. So most people never see a wild Tasmanian devil, you can go see them in wildlife parks and that sort of thing but they are otherwise quite secretive nocturnal animals.

They are quite impacted by quite a unique disease called the Tasmanian Devil Facial Tumor Disease which is cancer but it’s cancer that’s transmissible. So, devils that come into contact with one another during feeding or reproduction often bite each other and this cancer, mostly, is localized around the face and the mouth and when they bite each other, they can actually transmit cancer cells to the other individual that gives that individual cancer and that has had a huge impact on devils. We have seen about an 80% decline in devils across the state for the last 20 years or 25 years.So, it’s quite a significant conservation issue for them but also an unusual type of pathogen infecting a wildlife species.

Richard Jacobs: Do you think that means, I know this probably getting very esoteric but I don’t know, would a Tasmanian Devil be able to steal an organ transplant from other Tasmanian devils because maybe they can bite each other. One tolerates another’s cells and not have an immune response that’s strong enough to get rid of them. Perhaps they are able to do what we couldn’t or other animals couldn’t.

Scott Carver: Probably not. So, one of the things that cancers do because technically other cancers can be transmissible and there are certainly cases of like surgeons working on cancers that have accidentally stabbed themselves with a needle that’s been in contact with cancer and transmitted that to themselves but for the most part, cancers don’t have similar mechanisms of like transmission or to support transmission. But one of the things that cancers do to avoid the host’s immune system is that they downregulate the molecular markers around the surface of the cells called MHC. MHC basically is sort of a recognition marker that the immune system can tell what is like, what is yourself versus what is a bit foreign and because these cancers have sort of the ability like, to downregulate that they basically are telling the immune system that they belong in that host as well. So, if you were to transplant an organ, however, that wouldn’t, they’d behave differently that they would be recognized by the immune system and would be attacked by the host immune system and the only way you could regulate that like with humans would be to give immune suppressants.

Richard Jacobs: I guess that’s a special case that they could transfer cancer. I didn’t know that it could be transferred on certain occasions in people or in animals and that’s why I thought that.

Scott Carver: No, that’s okay. It’s a good question.

Richard Jacobs: Do you see any or do you know of any scientist who focused on the physiology or the various aspects of the pouches of marsupials. Is there something that you feel that maybe; so you need structure? I mean there’s probably a lot of learnings that could be achieved thereby studying them. Do you study them or do you know of anyone that does?

Scott Carver: Yeah, it’s not my area of super-strong expertise but I’ve got some colleagues that I can recommend who can probably speak to it better than I can or they could probably point you on to other people as well. So, I would be happy to suggest people.

Richard Jacobs: Okay, very good Scott. What’s the best way for people to find out more about your work or how to get in contact?

Scott Carver: I guess probably the best ways are through if they want to follow the actual research publications, things like Google Scholar, that they seem to do the best job of keeping up to date with those sort of things and my university website would be the other one and usually seem to cash a reasonable amount of fun, sort of media communication, so just Googling my name usually brings up some links that people can look up as well.

Richard Jacobs: Thanks for coming on the podcast and I know you are coming from far away and it’s probably an unusual time for you. so, thank you.

Scott Carver: Thanks a lot for everything Richard, I really appreciate it.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

In this episode, we discuss teenage social anxiety with Kyle Mitchell, a Tedx Speaker, author, and the founder of Social Anxiety Kyle. With a passion for solving mental… Read More

In this episode, we are joined by Matthew Moody, the President of Mental Health America of Arizona and a licensed counselor in Arizona. He has a Bachelor’s degree… Read More

Do pre and probiotics have healing and preventive powers? In an age of pharmaceutical solutions, finding sustainable and holistic health practices is critical. How can we leverage gut… Read More

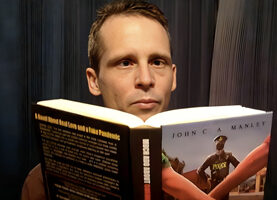

John C. A. Manley joins the podcast once again to discuss his daily email newsletter, Blazing Pine Cone Posts, and his work as a writer of fiction, freedom,… Read More

Bees are not alone in their fight to survive. While the backyard beekeeper might start with a pollinator garden, researchers are also busy strengthening and shoring up these… Read More

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get The Latest Finding Genius Podcast News Delivered To Your Inbox