Support Us

Donations will be tax deductible

Assistant Professor at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Dr. Augusto Rodriguez, talks about the scope of his work and research on different aspects of liver oncology.

In this episode, you will learn:

Dr. Rodriguez’s work centers around the goal of incorporating molecular information from tumors into tools that can be applied in the clinical setting to improve prognosis predictions, and developing novel methods for early detection of liver cancer.

The current gold standard for early detection of liver cancer is a combination of abdominal ultrasonography to look for evidence of small tumor formation, and blood tests to identify the levels of a certain protein known to be elevated in patients with liver cancer.

So, what’s wrong with the current gold standard? Dr. Rodriguez explains that in addition to operator error with regard to the ultrasound procedure, it requires patients to travel to an imaging center every six months, which is difficult to manage for many people. Due to the inconvenience and difficulty presented by compliance with the gold standard protocol, many people end up developing liver cancer that goes undetected for far too long.

A potential solution that Dr. Rodriguez has his eyes on is a technology called liquid biopsy.

In essence, it entails an analysis of tumor components within the bloodstream, such as fragments of DNA from tumors or extracellular vesicles released from tumors. The detection of such components in a blood sample taken at the point of care can detect liver tumors when they are very small, leading to better overall prognosis.

In addition, liquid biopsy may address another complication in the area of liver cancer treatment, which is the determination of how best to sequence the many therapies that have become available in recent years.

Dr. Rodriguez discusses a number of fascinating topics. Tune in for all the details.

Available on Apple Podcasts: apple.co/2Os0myK

Richard Jacobs: Hello, this is Richard Jacobs with the Finding Genius podcast. I have Augusto Villaneuva Rodrigues. He is an assistant professor at the Icon School Of Medicine at Mount Sinai and he works on liver-related issues, diseases. He is a hematologist and he also deals with oncologists, liver cancer type issues. So, Augusto, thanks for coming.

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: Thanks for having me.

Richard Jacobs: What’s your; in a bit more detail, what’s your work about, your research about?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: So, I work on different aspects related to liver cancer and I would say that the general scope of my work is trying to incorporate molecular information from the tumor into that can be applied in a clinical setting to improve prognosis prediction, prediction of responsive therapies or most recently, I’ve been very interested in trying to develop novel methods for early detection of liver cancer.

Richard Jacobs: So, liver cancer; who does it strike? Is it older people? Is it people that drink a lot of alcohol? What seems to be the precursor?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: So, it’s extremely rare to develop liver cancer if you have a healthy liver. It is very rare. So most of the patients with liver cancer have underlying liver disease, mostly sclerosis and the cause of this can be either by Hepatitis, Hepatitis B or Hepatitis C, alcohol use disorder or more recently, a cause of liver disease and also liver cancer that has emerged and has increased in the last 10 to 15 years is what’s called non-alcoholic scleral hepatitis and that’s essentially the abnormal passage of fat in the liver that induces chronic inflammation and sort of the predisposition of that patient to develop liver cancer. Now, non-alcoholic scleral hepatitis is relatively frequent but the number of these patients that end up having liver cancer is very rare. So, the challenge is can we identify those patients that are higher risk in developing tumors that we can enroll in what is called surveillance programs.

So, in surveillance programs, what we are trying to do is follow these patients closely so we can take the tumors when they are very small and they are potentially curable. So, worldwide, when we look at the numbers of the patients of liver cancer patients, you see this, a lot of liver cancer where there is a lot of liver diseases. For instance, in Asia, mostly China and sub-Saharan Africa, the number of people with chronic Hepatitis B infection is very high and that is why there is a lot of liver cancer in these areas. In western countries and the US, the main causes of liver cancer are mostly Hepatitis C but that has changed because now there are very effective treatments to cure Hepatitis C and that is what I mentioned before about non-alcoholic scleral hepatitis as emerging as one of the major causes of liver cancer in western populations.

Richard Jacobs: So, at what point does Hepatitis turn into liver cancer? Doe, a person has to have it for years? Again, how does it happen?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: Yeah, so the natural history of liver cancer, it takes a lot of years. So, on average, from the time that you get the infection with Hepatitis, either B or C until the time that you get liver cancer, you can spend 30 to 40 years. So, between that time is when you have chronic inflammation and fibrosis that is a micro-environment, the milieu that favors and we don’t entirely understand which ones are the dominant molecular arteries that happen during these years that end up favoring developing liver cancer but this is a very large, a very long, timespan since you get the initial damage to the liver before you get liver cancer and that’s precisely the rationale for implementing early detection programs.

So, for instance, in patients that have chronic sclerosis due to Hepatitis B or Hepatitis C, these patients are recommended to undergo surveillance. So, every 6 months, they do an ultrasound of the abdomen and some blood tests and the objective of that is to detect the tumor when they are very small because we know that they are at a high risk of developing liver cancer. So, when we detect the tumors when they are small, the possibility of curing these patients is very high. Now, one of the things we are doing at the lab is trying to develop new tools to improve that process. So, the current gold standard for early detection of liver cancer, as I told you, ultrasound and a blood test that analyzes the molecule of the protein.

Now, the problem is that ultrasound is very operative, for an ultrasound the patient has to go to a tertiary center to do the ultrasound, some patients live far away and they have to be done every 6 months, so it’s not very easy and actually there is a significant problem of implementation of these surveillance programs. So, people, despite they are at risk, do not enroll in these programs that detect the tumors in the early stages. So, we are looking at a technology that is called liquid biopsy that essentially entails the analysis of tumor components that are released to the bloodstream. It could be either fragment of DNA from the tumor or it could be vesicles released from tumor cells that can be isolated in the blood and we do a number of analysis, mostly sequencing-based that detects products that are specific to the tumor that can allow to identify or diagnose this tumor to detect them when they are very small.

Richard Jacobs: When you say products, are these extracellular vesicles that come from the tumor cells where it is something just shed from the tumor-like the actual cells themselves?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: Yeah, so with the vesicles, most of them are actually secreted by the tumor cells and it has been sure in other tumors, for example, pancreatic cancer has been shown that these vesicles are critical to prime distant tissues for metastasis to develop. So, the content of these vesicles are active or functional. I the case of liver cancer, we are not sure these may be functional at least when we use them as early detection biomarkers. But certainly there, we can detect products in these vesicles that are specific to liver cancer. The main advantage is that as opposed to having the patient coming to the hospital to make the ultrasound every 6 months, you can just collect the blood at the point of care which is much more convenient for the patient, you send a sample to central lab, run the analysis and you provide the estimation of risk. If you think about it, the paradigm for early detection, so what we do, in terms of surveillance programs hasn’t changed significantly in the last 20 to 25 years.

Richard Jacobs: You know, what would be really great; how they have those continuous Glucose monitors, if they had ones that were tuned for particular cancers if someone had that, then they could always be monitoring them and any upticks or changes would be reported right away.

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: Well, maybe not like continuous monitoring because it doesn’t make a change if you detect a tumor today or tomorrow but certainly if you have a device that can connect to your phone, you take your tiny amount of blood and you can analyze or get it analyzed and you get a report instantaneously will be extremely useful and will facilitate to detect tumors when they are curable.

Richard Jacobs: That’s true. So, right now, for liver cancer, how is it or when someone has it or doing early surveillance, is it surveillance biopsies or is it blood, are you going to a lab to get it taken, how is it right now?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: ow, what people do in terms of surveillance is they go and get an ultrasound to get an image of their liver. So they look at the liver to see if there is any nodule there and if a nodule is detected, then that triggers additional confirmatory diagnostic procedures. It can be a biopsy, it can be an MRI, it can be a series of tests depending on the characteristics of the patient but early detection is key because the prognosis of the patient is very different whether the tumor is diagnosed at the early stages or advanced stages. So that’s why it’s so important to have these patients at risk so that we know they are at high risk enroll in these programs so we can increase the chances of being cured with mostly surgical protection or some of them may be benefitting from transplants.

Richard Jacobs: So what’s your focus right now? Is it early detection or is it the particular pathways by which the tumor cells show their hand and say hey they are there at any point?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: We are working a lot on early detection and traditionally these studies have been difficult to conduct because what you want in early detection is to diagnose and detect tumors that are at early stages. So, when we do the studies, you need to enroll patients with small tumors or relatively small tumors because that’s the true challenge. So, your marker has to work with patients who have up to 2 cm liver cancer. So, to collect, to enroll or to have these patients studied is not easy so that’s why the main focus now is to expand on that. We’ve been collecting blood from patients for almost 4 years now and we have a decent amount of patients who fulfill that criteria. There’s another thing that is very interesting is that in the last 4 years there have been dramatic changes in the management of patients with liver cancer in terms of systemic therapies. So until 2016, there was only one systemic drug that shows efficacy to improve survival in patients with liver cancer.

So, that change is significant again in the last 4 years and now there are 9 drugs that have been approved by the FDA because they are effective in treating patients with advanced disease. These are different points of setting, if not for early detection, these patients would have advanced and so much more disease and the prognosis is worse. So, one of the challenges that we have now is, so we have many different therapies that were tested in parallel, so they were not tested one against the others because in typical trials, most of them run in parallel. So, it’s unclear which is the best way to sequence therapy, so what order the different treatments should be applied to the patients. One way to approach that problem is by developing biomarkers of response. In other words, you have a patient, you do a test.

In our case, we are looking at relating two more DNA and based on the mutation that the patient has, with the mutation profile we can undertake in the blood, we can estimate which is the best therapy or the therapy that provides the highest chances of that patient responding to that therapy. So once you do that, you can provide an organized structural way to allocate sequential therapies based on the likelihood of response using specific cases of tumors, in our case, again is a mutation on the basis of circulating two or more DNA

Richard Jacobs: So, at what point are you able to catch the tumor. Do you express it in terms of the number of cells that constitute them or if it’s only one tumor, it’s not multiple and there is no metastasis, how do you characterize if you’ve caught them and at what stage?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: Yeah, we’ve, circulating two or more DNA, you are able to detect tumors when they are as little as two centimeters in size. So, liver cancer with a size of potentially only 2 cm can be cured. So, we are talking about stages where they are very early and very small so that you can certainly cure the patient. Now, the thing with multiple tumors and metastasis is that and then the original thing that we would be working on is, so when you have a patient, you do a biopsy, for example, and you do mutation profiling and you analyze, you detect whether the patient has a mutation in 53 or a mutation in bowel or all the mutations that we know are prevalent in liver cancer. The question that we have is so what happens if you do a biopsy on a different tumor nodule where the metastasis is or in a different area of that specific tumor nodule. In other words, how heterogeneous tumors are.

So, would you get the same information or they are so heterogeneous that depending on the biopsy, you get different molecular information? What is critical about that is there may be mutations or molecular alterations that predict response to a specific therapy. So, if that alteration is present in one nodule and not in the other nodule, it does matter when you do the biopsy. So, we try to address that doing an analysis to determine heterogeneity and we enroll 14 patients and we do multitudinal sampling of this specific specimen. So, if there are 14 patients of liver cancer, we probably easier the nature of communications, and what we found is that 20%, 30% of the cases they are significant tumors with heterogeneity. So, in those cases, it does matter where you do the biopsy not only in terms of the specific alterations that you detect for the tumor but the actual immune infiltrate or the degree or the amount or the quality of the interaction between the tumor cells and immune cells are different in the different areas of the primary tumor nodule.

Richard Jacobs: How do you characterize the difference in the immune response within a given tumor or within proximity of it?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: So, for example, we have this patient that, so they had a fairly large tumor. We are talking about, the diameter I think was like 6 or 7 centimeters. We took; so we sampled 5 different regions of that 6-centimeter tumor. One region, when you do this, one region, whether you do this extra logically or when you do cell sequencing or RNA sequencing, we see there is a significant amount of immune cells, T-cells, heavily infiltrated region. Now, in a different region of the same tumor nodule for the same patient is barely infiltrated with immune cells. Ow, if you think about deriving biomarkers of response to new therapies, in the case that specific T-cell sequences or TCR achronality will define or will predict response to immune-based therapies and these patients particularly will make a huge difference if you did a biopsy in that region which is heavily infiltrated as opposed to the other region that is barely infiltrated. Now, this is not very common, it doesn’t happen much but in 20%, 30% of the patients, you can find these huge discrepancies of the amount of immune infiltrate they have in the same tumor nodule.

Richard Jacobs: This can happen, what, in a 2 cm sized tumor?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: It can happen but it’s not as frequent as with other tumors. So the degree of heterogeneity scales up with tumor size.

Richard Jacobs: Okay, that makes sense. Have you been able to; has anyone looked at 3D at various tumors and seen the heterogeneity spatially? Does that tell you anything? How does the heterogeneity grow as the tumor grows? Is there a certain point where the metastasis will start to form? Can you look at the heterogeneity and say, alright it’s getting ready to metastasize?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: In liver cancer, there are not that many studies because, with human cells, it’s very difficult to get that 3D information of tumors but certainly and this is the impression when you look at inter tumor hydrogenating, they are only, what I talk about, whether you do a biopsy, you can get a different result but if you look at it as a proxy of cancer evolution, certainly, the tumors that are more heterogeneous, the possibility of a clone of cancer cells emerging and being more aggressive, hence more prone to disseminate them from metastasis is higher. So, again, I don’t think there is compelling data on that but based on our study, we can say that the amount of inter tumor hydrogenating scales with the likelihood of a tumor being more aggressive.

Richard Jacobs: Okay, it makes sense. So what’s the next step in your analysis? What are you trying to figure out? Do you want to take a blood test where people can tell whether they have this tumor or what’s the next step for you? What are you trying to evaluate?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: Right, so we have a pilot study where we derived these markers for early detection of liver cancer on, we thought it was 200 patients and now we are trying to have a decent cohort of 1000 patients. So, with that, the little validation is significantly higher and is confident to pursue marker development and develop a more deployable test, for personal practice, it will be higher. So we are trying to expand and further validate our marker in different cohorts. Again, it’s always nice when you have patients from different centers, and let’s say you put your marker to the test to make sure it works despite you that you test it in different scenarios. So, that’s one thing where we are very interested. The second thing with the inter tumor hydrogenating story is that I told you we did the study in 14 cases.

We have expanded and we have now, around 80 patients who we are sampling and we are going to see if we can, again, estimate the degree of inter tumor hydrogenating and how it correlates with aggressiveness and more importantly, with the response to systemic therapies and that’s another thing that we are still working on and the final thing that we are very interested in is connecting both worlds. So, can we use the information from the liquid biopsy, the mutation profiling or the vesicles that are released by the tumors to quantify or estimate the degree of inter tumor heterogeneity because if you think about it, to biopsy the same tumor in different areas, that kind of practice is not feasible? We did it because we were dissecting specimens, so the tumor is out of the patient, it’s easy to take 5 regions of the tumor but when you do a biopsy, it’s not realistic to think about doing 5 biopsies on the same patient.

So, we need tools to estimate easily inter tumor heterogeneity without the need of doing multiple biopsies on the same patient. So those are kind of the 3 things that we are working on at the moment.

Richard Jacobs: So, what does it mean for a tumor to be heterogeneous? It just is a different gene expression in the cell types. Do you look at the degree of gene expression? Are there certain lines of change that are evidenced as the tumor, who has characterized what heterogeneity means, it looks like?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: Yeah, you can have two levels of heterogeneity. One is that the tumor cells evolve over time and you essentially have, at the gene expression level where we have that. So the tumor cells are different and the second thing with heterogeneity is that you can have the tumor microenvironment that supports, the tumor cells can be different in different regions. So, for instance, I mentioned the immune cells, the immune system, it can be different for different regions but this can also happen with endothelial cells and also cancer-associated fiberglass. We do that when we do single-cell RNA sequencing, we can quantify the contribution of tumor cells as opposed to the tumor-like environment to the genomic signal that you get in each of the samples that you analyze. So, the contribution of this micro-environment and these known tumoral components.

For example, tumor evolution has been barely studied in medicine as is liver cancer. So certainly the quantification of that if it was in terms of cellular components, that ecosystem of different cells that form a given tumor will help in providing potentially new therapies.

Richard Jacobs: So, what have you seen? How does the marker change as the tumor grows? Is it just more one type of, I would guess it’s very complicated. I don’t even know if there’s any correlations or general statements you can make but what’s been observed?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: In terms of? Sorry…

Richard Jacobs: In terms of what is given off by a tumor as it grows? Does it just give off more extracellular vesicles? Does it give off very particular types of metabolites or other signals as it grows, as it becomes more heterogeneous?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: Yeah, we haven’t looked at that extensively. But generally what you have is as a tumor grows or evolves, because it may evolve without growing too much but what you get is a clear different mutation profile. So you have a set of mutations that are common to all the tumor cells and those are found in mutations that are shared in all the cells and then a group of two more cells acquires, it’s a random effect. It acquires a set of new mutations that are not present in another let’s say two more cells of the same nodule. So those mutations are again, losses of potential tumor suppresser genes and what ca provide specific growth advantages to the tumor cells. Now, in other parts, just a little bit before gene mutation, you will get expression or DNA changes and we are starting to look at that.

So, how that DNA mutation heterogeneity can contribute to the emergence of aggressive clones when the tumor is still to be determined. But certainly, it can contribute and it’s not only about mutations, the field has been very dominated by focusing on DNA mutations but again, whether other layers of molecular information or gene expression or DNA mutation or even the continuation of the tumor microenvironment to this process is still not very well established. Another thing that we found that is very striking and we did a follow up on that but for time constraints. One of the things that are very strange and interesting is that when you look at the different regions of the same tumor nodule and looking at the single-cell data, you find that in addition to the tumor cells being different, the cells from the micro-environment may also be different. I’m talking about cancer-associated fibrosis, for example.

There is an emerging study in other tumors that show that they are different types of cancer-associated fibrolase. So despite these are not malignant cells per se, they are not transformed, they don’t have mutations, they do not operate under normal conditions when they are embedded in the context of a tumor. So that is very interesting because if you can somehow target or affect some of these known tumoral components, you may have also, an anti-tumoral effect but that has never been explored in liver cancer.

Richard Jacobs: So, I don’t know what you think is going to be the first part of the progress? What mutations have been looked at? I mean, there was an article that, recently in Science, talked about bacteria living inside of tumor cells, not just around them. Is anyone in the liver arena looking at the micro-biology of tumors, in them and around them?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: Yeah, the diameter, I think one of the first studies was done, I suppose in 2012 by a group from Colombia and he showed that essentially when you contaminate the gut of animals, of mice, you are able to modify the progression of proto-cellular progression of liver cancer. So there are many people working on trying to assess the contribution of the micro-bio in not only liver cancer development but also in liver cancer progression. Yeah, I saw that study, it was very interesting to have that in tumors. In patients with liver cancer, remember I told you that the majority of these patients have chronic liver disease, mostly sclerosis, well, in patients with sclerosis, the barrier that let’s say separates the gut from the liver is a little bit loose to some extent. The possibility of some bacteria from the gut from being translocated to the liver is a little bit higher.

So, people are trying to understand what if these translocations of the bacteria is somehow primarily involved in the risk of developing tumors but the data is still derived from animals and we need, I guess more data in humans to make sure that this could be a potential way to prevent liver cancer development by targeting these micro-bio.

Richard Jacobs: Interesting. So, I don’t know, is there any big signal that’s coming from the liver when it’s in disease stage pre-cancer versus once you have a tumor or two and is that being looked at or is it just the tumors come and okay, now it’s worth looking at?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: Before you have full-blown liver cancer, there is a previous pre-cancerous lesion called the spastic nodules. They are very difficult to study in humans because they are very small and generally you don’t see them. When you see them is when you do, for example, a liver transplant and you have an explant of a sclerotic liver and you just start doing extensive surgical analysis and within that analysis, you can start to see small nodules, I’ talking about 1 centimeter or smaller that are just full size. So there is a group of bottle sides that are not normal but they are not entirely malignant, it’s an intermediate phase and there have been classical studies that show in some of these particles, as you can see early, very early very well-differentiated tumors within the spastic nodule. So, there is no question that these are perennial plastic lesions. Now, the attempt to characterize which are the first very initial alterations that make those spastic nodules trying to well differentiate by cellular carcinomas, there are not that many studies.

The only, I would say, clear gatekeeper lesion or mutation seems to turn promoter.

That can be found in up to 20% or 30% of spastic nodules. Now, we are trying to see now if, in early detection studies, we can get some signals that are being derived from the spastic nodules but it is not easy because as I mentioned, to characterize is not just to imbue, it is very difficult. It is almost impossible; you can have histology but certainly, it would be fantastic to have a readout to identify the patient with these spastic nodules because certainly, these patients are at high risk of developing liver cancer.

Richard Jacobs: Yeah, it makes sense. So what do you see ahead for the next few years? Are there any near-term breakthroughs that you are near to be approaching?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: I think that to have a liquid biopsy-based, I mean we are working with vesicles but other people are working with DNA mutation and cell-free DNA, I think that will be a major game-changer in the management of liver cancer. You have an easy liquid biopsy test for early detection. That’s one and the second thing is that the clinical benefit, the improvement in survival has been achieved at least in a subset of patients that are treated immune check inhibitors is dramatic and the consequence of that is that now these therapies are being tested heavily not only in patients with advanced-stage but also patients with intermediate stages or early stages who have therapy after surgical reduction.

So, it would be great to understand how or which are the patients that benefit from these therapies because not all of them benefit. 20%, 30% of patients are steady and these patients do very well when they receive immune-based therapies alone or in combination with surgical procedures. So, I think there are two things that will be game-changers in the near future. I’m talking about 5 years from now, will be that early detection tool based on liquid biopsy and the application of immune-based therapies to earlier stages so we can maximize the outcomes of patients that are currently receiving conventional therapies with protection or immunization. So that I think will significantly improve outcomes in these patients.

Richard Jacobs: What’s the normal prognosis for liver cancer. I know, the liver regenerates, it gets resected for sure, not part of it at least in liver cancer but is liver cancer particularly fatal or what are the stats on it?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: If you look overall, what I mean overall is if you don’t analyze by tumor stage, the prognosis is quite bad. So, I would say that global data, the 5-year survival of HTC as a whole is around 18% which is the second most lethal.

Richard Jacobs: It’s bad

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: Yeah, single most lethal tumor after pancreatic cancer. So, it’s a very lethal tumor. Now, when you look at when you stratify a patient’s stage, the patients that have early stages they do very well. So the 5-year survival, when you have an early tumor that is resected for surgery, is more than 70% which is very good. That is why it’s so important that we implement surveillance programs to have many more patients being diagnosed at early stages than advanced stages. But still, it is a very deadly disease, unfortunately.

Richard Jacobs: Yeah. So what’s the best way for people to learn more about you, your work, and keep tabs on liver biopsies and development of them?

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: I guess that we are very active, policy papers on studies that we do and we have a webpage on the lab, there are a couple of resources, there are a couple of YouTube videos where we explain some of the results that we have. So we try to be quite open about our results and disseminating different conferences. The last Liver Cancer Association meeting is happening virtual as a result of the pandemic. In September, we are going to present 3 studies there. So we try to be active in disseminating our results.

Richard Jacobs: Okay, very good. Augusto, I thank you for coming. I appreciate it.

Augusto Villanueva Rodrigues: Thank you very much for having me, it’s been a pleasure.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

In this episode, we discuss teenage social anxiety with Kyle Mitchell, a Tedx Speaker, author, and the founder of Social Anxiety Kyle. With a passion for solving mental… Read More

In this episode, we are joined by Matthew Moody, the President of Mental Health America of Arizona and a licensed counselor in Arizona. He has a Bachelor’s degree… Read More

Do pre and probiotics have healing and preventive powers? In an age of pharmaceutical solutions, finding sustainable and holistic health practices is critical. How can we leverage gut… Read More

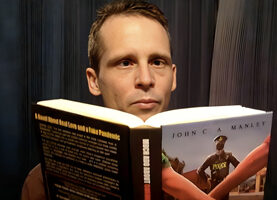

John C. A. Manley joins the podcast once again to discuss his daily email newsletter, Blazing Pine Cone Posts, and his work as a writer of fiction, freedom,… Read More

Bees are not alone in their fight to survive. While the backyard beekeeper might start with a pollinator garden, researchers are also busy strengthening and shoring up these… Read More

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get The Latest Finding Genius Podcast News Delivered To Your Inbox