Support Us

Donations will be tax deductible

Professor Vythilingam started working with parasitic diseases in the early 1980s and now studies the recent upsurge in Plasmodium knowlesi in humans, which is a malaria originating in monkey hosts.

In this podcast, she discusses

Indra Vythilingam is a professor of parasitology at the University of Malaya. Malaria is not a virus; rather, it’s a disease caused by a parasite of the Plasmodium species that follows a host and vector life cycle. She started working on malaria the early 80s. In the early 1990s, she worked on a study with insecticide-treated mosquito nets, proving their efficacy. However, in the years since, malaria-infected mosquitoes have adapted their behaviors and evolved in Malaysia to bite earlier in the evening and outdoors.

Furthermore, she explains that malaria is traveling from monkeys to mosquitos to people in Malaysia, a discovery made in 2004. Previously it was thought that humans could only catch malaria from a few specific species thought of as the human malaria parasites. However, a 2004 paper showed the simian parasite, Plasmodium knowlesi, had been transmitted to humans.

Professor Vythilingam explains that the human malaria has been almost eradicated from the area, but they now have this difficult development to face. She discusses what measures she and her colleagues are hoping to take after the COVID-19 virus pandemic slows enough to allow them to return to the field.

For more information, search for Indra Vythilingam in Google Scholar and other such research-accruing sites.

Available on Apple Podcasts: apple.co/2Os0myK

Richard Jacobs: Hello, this is Richard Jacobs with the Finding Genius Podcast. My guest comes from far away. She’s in Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia at the University Of Malaya. Her name is Indra Vythilingam. She’s a professor of parasitology. And we’re going to talk about her work in parasitology. So, Indra, thank you for coming. So, if you’re in Malaysia, it must be like the very, very early morning to you, right?

Indra Vythilingam: Yes, it’s 5 AM.

Richard Jacobs: That’s very early. Thank you for getting up so early to do this, I appreciate it very much. Indra, tell me about your work with parasites. How long have you been working with, what got you interested in them?

Indra Vythilingam: Okay. I’ve been working on malaria parasites and their vectors for a long time. I started working on them in the early 80s and in the early 1990s, we had a project on the use of insecticide-treated bed nets for malaria control, so we were the first to do it in Malaysia to see how effective the insecticide-treated bed nets would be. And at the end of the project, we found that there is a significant difference when people use insecticide-treated bed nets combat to [inaudible – 0:01:19.8]. So, my work on malaria starts way back from then.

Richard Jacobs: So, people would use these nets that are treated with anti-malarial substances, or what do the nets look like? When are they used?

Indra Vythilingam: They are treated with insecticides, so when the mosquito comes to try and bite the people, it will move up and down the net, so the net mosquito picks up enough insecticide to kill itself.

Richard Jacobs: So, is this mostly used when people are sleeping or when do they use it?

Indra Vythilingam: Because the malaria mosquitoes, in those days, they come to bite people late in the night when people are indoors when they are going to bed. So, that is why the nets became effective and they were able to bring down the cases of malaria. Prior to the use of insecticide-treated bed nets, they used to do residual spraying of the walls, that mean they spray the walls indoors the walls of people’s houses because the mosquitoes had a habit of resting on the wall, going to bite the person, resting again before it flies off. So, the mosquito picks up enough insecticide to kill itself but after many years of spraying, the mosquitoes changed their behavior. They usually come indoors, they will bite and fly out. So that is when insecticide-treated bed nets came into play.

Richard Jacobs: You said the mosquitoes changed their behavior?

Indra Vythilingam: Yes, because nowadays, the mosquitoes are biting earlier in the night especially after the use of insecticide-treated bed nets, the mosquitoes are biting earlier and they are biting outdoors. So now, if you look at the research that was done in the 80s, the 90s and then if you start looking at the research that was done in late 2000, you can see the difference in the biting habit of the mosquitos.

Richard Jacobs: How could the mosquitoes know to change their habits? Do they smell or sense the insecticide?

Indra Vythilingam: It is like not all mosquitoes get killed. So, these are mosquitoes like their genes are carried down. So, the mosquitoes that survived, so they will know that is the behavioral change of the mosquitoes, they are smart themselves. So, that is why nowadays, in Southeast Asia, for malaria elimination, we are having a problem because the mosquitoes are biting very early in the night. They come to bite around 6, 7, 8 PM and the mosquitoes are biting more outdoors than indoors.

Richard Jacobs: Is there any benefit of that, people are indoors, are there less mosquitoes that come in?

Indra Vythilingam: Most rural areas are outdoors during that time. They are chatting with friends and they congregate together so most of them are outdoors in the early part of the evenings and that’s when they get bitten. And of course now, in Malaysia and in Southeast Asia, we now have a problem with simian malaria parasites that are transmitted from the monkeys to the human via the mosquitoes.

Richard Jacobs: How do they transmit it to people from the monkeys?

Indra Vythilingam: Okay. So, the mosquitoes, the Anopheles mosquitoes pick up the parasites from the monkeys and transmit it after they go through the cycle in the mosquito, they become the infective stage, that’s sporozoite stage and then, they are able to transmit the parasite to the human when they bite a human. Now, this is something that was actually discovered way back in the 1960s by the Americans.

Richard Jacobs: So, what’s the difference between a mosquito biting someone directly and that going into a monkey first? Does that make it more virulent?

Indra Vythilingam: No. There are certain malaria-parasites that are found in the monkeys and in the 1960s, when the work was done in the laboratory, some of the scientists got infected with this monkey malaria parasite in the laboratory by infected mosquitoes so they were excited. So they came down to Malaysia and they wanted to do work on monkey malaria. So they did a lot of screening, they screened people, they looked for mosquitoes and they were not able to find any infected case. But in 1965, the first case of monkey malaria that was plasmodium knowlesi was found in an American surveyor who was living or who was working in the jungles of Pahang in Malaysia. He was fortunate that he went back to America in time when he fell ill and it was in America that they discovered he was actually suffering from plasmodium knowlesi because when you look at these malaria parasites under microscopy, they are very closely lookalike, the human and the simian malaria parasite looked very much alike. So, it was not easy to tell apart. But when they inoculated the blood into the monkeys, the [inaudible – 0:07:01.1] monkeys die and the long-tailed macaques, they survived and they showed a 24-hour cycle and thus, they knew that they were dealing with the simian malaria parasite, plasmodium knowlesi.

So they came to Malaysia and they did more work, they did not find any cases but they found a lot of new parasites in monkeys and they did find mosquitoes with the parasites but these mosquitoes did not come to bite a human. So at that time, they made a ruling or a hypothesis that simian malaria will remain with the monkeys and it is only human malaria that will be transmitted to the human. So that went on until 2004 when a landmark paper was published to show that plasmodium knowlesi, a simian malaria parasite was being transmitted to humans. So after 2004, a lot of work was done in Malaysia. We do molecular detection and we now find that there are many cases of plasmodium knowlesi in humans. So we have almost eliminated human malaria in this country but we have a large number of plasmodium knowlesi among the human.

Richard Jacobs: So, I’m trying to understand why this is a big problem. Do the monkeys come in contact with humans a lot or is it …?

Indra Vythilingam: With deforestation and changes in the landscape, the monkeys have come more towards the forest age and the farms and plantations. And the mosquito vectors have followed these monkeys. So now, the monkeys, the mosquitoes, and the humans are in close contact with each other. So humans are getting infected when they go to the forest or when they go to the farms or plantation. That is what is happening.

Richard Jacobs: I see, okay. And malaria was almost eradicated from Malaysia?

Indra Vythilingam: We have not got [inaudible – 0:09:17.2] this year but now with COVID-19, I do not know what is going to happen because you must be malaria-free human, malaria-free for 3 years before WHO can give you the malaria elimination status.

Richard Jacobs: So, you want the WHO’s blessing to say that Malaysia is malaria-free?

Indra Vythilingam: WHO is the body that gives the status of malaria-free to all countries, so Malaysia is in the process. But we have a large number of plasmodium knowlesi and now we also find there is another simian malaria parasite that’s Plasmodium Cynomolgi, it is also being transmitted. And the simian malaria parasite is not only found in Malasia but it has been reported from all countries in Southeast Asia with the exception of [inaudible – 0:10:18.3] Timor Leste, perhaps they have not looked for it. And Malaysia perhaps is finding more cases because we are using molecular technics and also because the number of human cases of malaria has come down so perhaps people are losing their immunity.

Richard Jacobs: So, the fact that mosquitoes are biting early evening now and doing it more outside, what the countermeasure to that? What else has changed in those mosquitoes besides that?

Indra Vythilingam: That is why we are having a lot of problems. We do not know how to prevent the mosquitoes from being bitten. Of course, there are repellents, I know in America, they use a lot of repellents to keep away the mosquitoes in the summer. But repellents are not cheap and people living in rural areas really cannot afford to buy these repellents. Repellents are expensive. One of the best repellents is, of course, a good repellent and it’s expensive. So people are not going to buy repellents and use them, so that’s why we are still thinking about what is the best method that can be used to prevent outdoor biting mosquitoes. It is not easy to get rid of mosquitoes that are biting outdoors and are biting in the early time, so this is a challenge for us.

Richard Jacobs: If you’re thinking that mosquitoes were selective for the ones that don’t go in the houses and stick to the walls and bite people, maybe there is something else different about them genetically, fanatically, etc. Has anyone characterized them to see if they’re exact same as the mosquitoes that used to bite before or are they different?

Indra Vythilingam: As you mentioned, these are the ones that were not exposed to the insecticide [inaudible – 0:12:15.8] that is being smart so we referred to as behavioral changes and so these are the mosquitoes that are now biting outdoors and in the early part of the night. That’s why I always say that mosquitoes are smarter than humans.

Richard Jacobs: Why are mosquitoes nocturnal? Why would they bite late at night before but now they bite earlier?

Indra Vythilingam: Among mosquitoes, again different species of mosquitoes have different biting times. For instance, Aedes mosquito, which transmits dengue, it bites during the daytime. It bites at dust and dawn. Whereas the Culex mosquitos which transmit Japanese encephalitis, they will bite at night. Anopheles mosquito — the Culex mosquito bites towards the early part of the night compared to the Anopheles mosquitoes. The Anopheles mosquitoes use to bite in the later part of the night, perhaps they found that was the best time so they come out late at night and bite. But when people start to take protective measures, the behavior of the mosquitos change.

Richard Jacobs: Yes, I understand that. I just wonder if anything else about them has changed, is anyone observing the mosquitoes and looking at their DNA and looking at the epigenetics if they have them and seeing what changed them, are their eating habits different, what’s different except the biting time, maybe there are other things that have come along with it that could be used as an advantage to get rid of them?

Indra Vythilingam: We have also found that even among the Anopheles mosquitoes, the simian malaria parasite is transmitted by a certain group of the Anopheles mosquitoes, not all. These mosquitoes, we refer to as they belong to the lupus virus group of mosquitoes and these mosquitoes bite both the monkeys and the human. So, in the 60s, it was very difficult for us to come across these lupus virus group of mosquitoes but now we find that the lupus virus group of mosquitoes is more common than the other malaria mosquitoes. As I said, it could be due to deforestation, their habitats have been changed, the monkeys have come out and so now, these mosquitoes have a chance of biting not only the monkeys but they have also adapted biting the human.

Richard Jacobs: So, what are some of the new strategies that Malaysia is looking at to reduce their effect to get rid of malaria now?

Indra Vythilingam: As far as Malaysia is concerned, they have done well with human malaria. They have managed to bring it down to very, very low level and they claimed that over the last 3 years, they have been free of indigenous cases of human malaria but now, Plasmodium knowlesi is — we have quite a large number, 89% of all malaria cases are actually Plasmodium knowlesi and we have a huge project in Peninsular Malaysia to actually study the vectors and to look at the distribution of the cases in Peninsular Malaysia because so far from 2004 until now, most of these studies were done in Malaysian Borneo, that is Sabah and Sarawak as Malaysian Borneo. Most of the studies have been done there, we have established the vectors there but very little is known about the vectors in Peninsular Malaysia. And so we have an acute project where we are studying not only the mosquitoes, we are also studying the genetic structures of the parasites and from the mosquitoes, the human, the macaques (the monkeys) and we are trying to put this together to see what is happening and we are also trying to develop a rapid diagnostic test because we feel that it is important to have a rapid test so that people can just take a drop of blood, put it on the dipstick and see whether the patient has the malaria parasite because microscopy is not going to be very useful because it’s not easy to identify between human malaria parasites or simian malaria parasites.

And also we have noticed that people are asymptomatic, which means they’re having parasites but they are not showing signs and symptoms. So, it is important to detect and treat people. That is one way …

Richard Jacobs: Treat what people, everyone, or asymptomatic people?

Indra Vythilingam: That is asymptomatic. If you happened to take their blood, if they have the parasite, they’re not showing signs and symptoms, it is advisable to treat them.

Richard Jacobs: But why? Is it transmitted sexually or what can an asymptomatic person will eventually get sick or what happens?

Indra Vythilingam: It could be that the parasite is at a very low level and so the people are not showing signs and symptoms and it’s also among the indigenous population, they may have built up immunity towards the parasite. So you may have the parasites but you won’t show signs and symptoms but you can be infectious to the mosquitoes.

Richard Jacobs: Okay. If the mosquitoes bite you, you can give them malaria. They won’t get sick with them, they’ll give it to other people?

Indra Vythilingam: Yes.

Richard Jacobs: Okay. I mean is that a major vector or what percentage of people are asymptomatic? Actually we are talking about the coronavirus and they’re going to quarantine asymptomatic malaria people now, what’s the plan there?

Indra Vythilingam: In those days, even when a patient had dengue, I remember in the 70s when a patient had dengue when he’s in hospital, he sleeps under a bed net. But these days, we don’t see such things happening.

Richard Jacobs: What happened?

Indra Vythilingam: If a person is having dengue in a hospital, if you go to the hospital, you would not see a person under a bed net. I do not know why they took it off but I mean in those days, I remember when I started my work in the 70s, when we went into hospitals, if a person is dengue, he will definitely be put to sleep under a bed net because they do not want the mosquitoes to bite him and transmit the infection to other people.

Richard Jacobs: So, what do they do now? Nothing?

Indra Vythilingam: I don’t know. Now, they are not.

Richard Jacobs: So, what’s your role in this? Do you want to advise the Malaysian government on what to do or are you studying the parasite itself for ways to counteractive, like what’s your major role in this?

Indra Vythilingam: Okay. Our major role is, of course, we are working with the Government of Malaysia and we’re working alongside with them and we tried to find answers for questions, we tried to find out what’s happening, what are the vectors that are present and is there any genetic difference between the parasites found in the mosquitoes, in the macaques, in the human. We are trying to study that, “Okay, what’s the difference between the genetic makeup of the mosquitoes that are of the parasites that are found in Peninsular Malaysia compared to those found in Saba and Sarawak. So, these are things that we are studying and we hope that our project fund — our funding started last year in 2019 and it’s supposed to run until 2022. But this year from March, from the time the lockdown started, we have not been able to go out to the field to collect any samples, so you see there is the backlog in our work. But we hope that by 2022, we can come up with some answers and we can perhaps think of what really can be done to review the number of severe malaria cases among humans.

Richard Jacobs: What happens when someone’s had malaria? Can they ever be cured of it?

Indra Vythilingam: Yes. They do treat — the people are treated and we are fortunate so far in Malaysia, we do not have problem with drug resistance, the Artemisinin Combination Therapy (ACT) has been effective and people can be treated. If they go early enough, they can be treated. So the death due to malaria happens when a person goes very late to the hospital, then sometimes they succumb to death. I would say that there was no mortality — mortality has been on the very low side. So if people are ill and they go to the hospital, they can be treated. There are drugs.

Richard Jacobs: What happens if someone’s treated for malaria and they are deemed to be cured, what happens if mosquitoes bite them after that? Would they still be able to start malaria up again?

Indra Vythilingam: No. If a person has been treated, that means he is clear of the parasite. But one should understand that the malaria parasite, we have different species of the malaria parasite, for instance, even among the human malaria parasite, plasmodium vivax, that parasite can remain — some parasites can remain in the liver, so that’s what we call as the Hypnozoite, it can remain in the liver of the human for a long time and all-of-a-sudden, one day, it could just be released from the liver and it can enter the bloodstream and the person can come down with Malaria. That is in the case of vivax. So, that is why when people get Vivax malaria, the treatment schedule is different. People are treated for 14 days to make sure that the drug has to clear off all the malaria parasites.

Richard Jacobs: Because then, they can’t be a reservoir of infection after that treatment?

Indra Vythilingam: But it does happen. Vivax malaria, it does happen from time to time that people can have a relapse without being bitten by the mosquito. It’s because of this stage of the parasite that hides in the liver of the human.

Richard Jacobs: So, what do you think is going to be a breakthrough once you’re able to get out and do sampling? What do you think is going to be the first step towards sampling down malaria again?

Indra Vythilingam: With simian malaria, we feel that more resources — it cannot be just researches looking on it and hoping to get a breakthrough. We can tell the controlling bodies of people are working to control the disease, so we hope that various bodies out there would play their role and not just say that, “Simian malaria is not part of human malaria and so it will not be taken into consideration when it comes to malaria elimination”. One thing that we feel very skeptical is that once you see you have eliminated malaria, everybody forgets that malaria so when a person comes down with malaria after going to the forest, nobody will think that he’s suffering from Malaria. Why? Because we have eliminated malaria and this poor guy may succumb to it. Why should we have anybody dying from malaria at this point in time? So that is our concern. We feel that at the back of our mind, we must let people know that simian malaria is going to be a force to reckon with and we need to take steps to try and overcome that problem.

Richard Jacobs: I don’t know if this is true but I’ve heard with like coronavirus, people being locked in their homes, monkeys running everywhere, perhaps the simian malaria is maybe greatly increased during this time. And then, when people come out, I guess for a time, they’ll have to beat back the monkeys or they may be everywhere, I don’t know. There may be a huge spike in it.

Indra Vythilingam: I mean luckily between the parasite and the virus, there are differences especially like with this coronavirus, it can be transmitted from human to human, it doesn’t go to a mosquito but in this case, for a malaria parasite, to get infected, the person, of course, needs to be bitten or the only other way is, of course, a mother who is having a malaria parasite, when she gives birth, the malaria parasite, especially at the last stages of giving birth, she can pass the parasite to the fetus. And also, if the person resists [inaudible – 0:25:58.6] too. But it is mainly true with the mosquito bite. So, the only thing is that we must always remember at the back of our minds that the two main malaria parasites that are affecting humans, the plasmodium falciparum and plasmodium vivax. 50,000 years ago, those parasites were found in the non-human climate and they jumped the barrier and they came adapted to humans. So, this is our fear that if we do not do anything now, maybe down the line these simian malaria parasites, plasmodium knowlesi, plasmodium cynomolgi may jump hosts and may become adapted to human. That is something because these parasites can mutate very far. So, we can say that eliminated malaria but after many years, we [inaudible – 0:26:53.5] malaria.

Richard Jacobs: Very good. Indra, what’s the best way for people to keep tabs on the work that you’re doing and to learn more about malaria? Where should they go?

Indra Vythilingam: Well, we publish all our papers that we work on, we make sure that they publish all our findings. It’s always published in all sub-journals. We present them at conferences and we do inform people on how are we obtaining the data that we have obtained.

Richard Jacobs: Okay, very good. Indra, thank you for coming on the podcast. I appreciate it.

(End of recording)

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

In this episode, we discuss teenage social anxiety with Kyle Mitchell, a Tedx Speaker, author, and the founder of Social Anxiety Kyle. With a passion for solving mental… Read More

In this episode, we are joined by Matthew Moody, the President of Mental Health America of Arizona and a licensed counselor in Arizona. He has a Bachelor’s degree… Read More

Do pre and probiotics have healing and preventive powers? In an age of pharmaceutical solutions, finding sustainable and holistic health practices is critical. How can we leverage gut… Read More

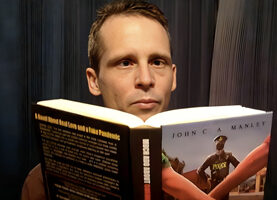

John C. A. Manley joins the podcast once again to discuss his daily email newsletter, Blazing Pine Cone Posts, and his work as a writer of fiction, freedom,… Read More

Bees are not alone in their fight to survive. While the backyard beekeeper might start with a pollinator garden, researchers are also busy strengthening and shoring up these… Read More

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get The Latest Finding Genius Podcast News Delivered To Your Inbox