Support Us

Donations will be tax deductible

Human beings enjoy a level of dexterity superior to most other species by virtue of what’s called the corticospinal tract, which is a projection that reaches from the motor cortex in the brain, down to the brain stem and spinal cord, and connects directly to the muscles.

As beneficial as this special pathway in humans can be, it comes at a cost: even a small amount of damage can have devastating results. When someone suffers from a stroke, it is this pathway that gets damaged and leads to many possible symptoms, including weakness, loss of dexterity, clumsiness, and the inability to isolate joint movements. The key to the best recovery from stroke is very early, very intense rehab, but it can be challenging to motivate people into maintaining such intense work.

Dr. John W. Krakauer works in the Brain, Learning, Animation, and Movement (BLAM) Lab at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, where he’s not only studying the differences between movement in health and movement in disease, but also exploring and testing ways of engaging post-stroke patients in the intense rehab routines necessary in order to help them regain as much movement and control over their bodies as possible.

He explains how important it is to create emotionally gratifying and motivating experiences for people early on in their recovery in order to engage them in ways that will best amplify the abilities they do have—the abilities they did not lose as a result of a stroke. The same idea applies to all types of neurological diseases and injuries, including traumatic brain injury, Parkinson’s disease, cerebellar ataxia, and multiple sclerosis.

At the BLAM lab, they are developing interactive, exciting, and engaging games specifically geared toward patients with neurodegenerative issues, encouraging them to perform miles’ worth of movement without even noticing it. They are also working on forming cohorts of people who have suffered from stroke and who could benefit from working together in multi-player games.

The idea is that this would build a sense of competition, thereby making it easier for people to sustain the level of rehabilitative intensity needed. Furthermore, by isolating problems with particular body parts to particular characters in games, each individual’s specific problem area could be addressed in the most effective way possible. Interested in learning more?

Tune in for all the details and visit www.blam-lab.org

Richard Jacobs: Hello! This is Richard Jacobs with the Future Tech and Future Tech Health Podcasts. I have a Dr Jon Krakauer he is from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Department of Neurology. Dr. Krakauer thanks for coming. How are you doing?

Dr Jon Krakauer: I’m very well, thank you. Thanks for having me on your show.

Richard Jacobs: Okay Yeah! So tell me about the brain learning animation and movement lab. The Blam Lab

Dr Jon Krakauer: Right! So we are lab based in the neurology department at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and we are quite broad-ranging and what we do we are in the broadest sense, interested in movement in health and disease, So how do you plan control and learn movement in health and then what happens to planning, controlling and learning movements after brain injury? I’m really interested in the science of movement and thinking of new ways to treat people and rehabilitate them to lose movement.

Richard Jacobs: When you say movement, you don’t mean exercise, you mean physical movement like walking

Dr Jon Krakauer: We’re mostly interested in reaching and grasping. That’s right, we’re interested in the control of the arm and of the hand and in the skilled movement of the arm and hand. We don’t really do lower body. There are other people at Hopkins that we collaborate that do, but we really do arm hands.

Richard Jacobs: So what kind of conditions cause a loss of movement and tell me a little bit about it. What happens?

Dr Jon Krakauer: Well stroke is a major cause of loss of control of the arm and hand, cervical spine injury, brain trauma, Parkinson’s disease, cerebellar Ataxia, multiple sclerosis. So there are many neurological diseases and also injuries that will affect your ability to move your arm and hands, but we focus on the main core disease that we study is a stroke.

Richard Jacobs: So what happens when someone has a stroke for instance, like what physically happens to cause a loss of the ability to move properly?

Dr Jon Krakauer: Well, a stroke, you know, as when you lose blood and oxygen to a particular part of the brain, a very common part of the brain that affected is the, at the motor areas and its outputs. And so commonly after a stroke, people will become weak and they will also lose dexterity. So even if they have not complete weakness, they just become clumsy and then you can also develop additional symptoms called synergies where you have these unwanted movements that sort of interfere with your ability to isolate your joints. So it’s really a combination of weakness, dexterity loss, and a kind of movement disorder. When you get these intrusive movement patterns, all of these were attributable to losing parts of your brain that transmit out to your spinal cord.

Richard Jacobs: Well, unintended movements, you mean like tremors or shaking

Dr Jon Krakauer: Not so much that it’s for example, you know, you try and extending the elbow and your shoulder flexes you try and just move your hand and your whole arm move.

So you lose the ability to isolate individual particular joints. You try and move one finger and all your fingers close. So you basically get these intrusive, unwanted, additional movements while you try to make a voluntary movement. So stroke patients have had find it very difficult to move one finger and keep the other fingers get enslaved and go along for the ride. So you’re trying just flex your forefinger and all your fingers.

Richard Jacobs: I just had an injury and then yeah it is hard to isolate certain muscles. And I’ve had a surgery or two where you want to move a certain muscle and you literally can’t like you just can’t make it move and you don’t feel like you’ve lost the connection temporarily to make something move. So I understand that what happens early after stroke.

Dr Jon Krakauer: And then when movement ability comes back, it can’t be as you just said you can’t isolate things as well. Other things come along for the ride and that’s sort of what I mean by this additional fat that loss like you just described. And then this is unwanted intrusion that comes along with the return.

Richard Jacobs: Okay! So what do you think is happening physically to cause that?

Dr Jon Krakauer: Well, we sort of have an idea that humans are particularly dependent on something called the cortical spinal tract, which is this projection from your motor cortex in your brain down through your brainstem to your spinal cord, and it connects you directly up to muscles and that gives us all the dexterity that we have, which is better even than chimpanzees, but the price we pay for having this system is that if you damage it, you’re devastated. So what seems to happen is that you lose this descending pathway that’s special in humans when you interrupted anywhere along its path after a stroke.

Richard Jacobs: So what happens in the stroke?

Dr Jon Krakauer: Well, there are two kinds of strokes. The most common kind it makes up about 85% of strokes is where a blood vessel is blocked by a clot or by atherosclerosis and so that part of your brain loses blood and oxygen and dies. So basically, a stroke is a lot of brain tissue through the deprivation of blood and oxygen. That’s the most common kind of stroke. And there are many causes for that. You know, cardiac conditions and other things. And then hemorrhagic strokes where you basically bust a blood vessel rather than block it. And so you bleed and that also can have the same effect because the blood exerts pressure on brain structures and even kills them. So whether you deprive an area of blood and oxygen or you flooded with high-pressure blood, the consequences can be very similar.

Richard Jacobs: So how does it causes loss of motion? Is it just because the brain’s not able to send signals properly, even though the plumbing is still there? I guess for a crude way to put it.

Dr Jon Krakauer: You’ve basically killed tissue that’s projecting down to the spinal cord, right? You’ve either interrupted the cables, the white matter, or you’ve killed the gray matter, but it’s basically the death of neuron tissue.

Richard Jacobs: So what are you learning or ways to modulate this effect?

Dr Jon Krakauer: Well, we’re just trying to find ways to have people try and get better with what they have left. In other words, you never lose everything. And then we need to find a way to sort of modulate and amplify the control abilities you have left with the remaining areas of your brain that have not been damaged. What we think is that you need to exploit that residual capacity by doing very intense rehabilitation very early of the stroke because of the diminishing return as time goes by to try and exploit these residual connections.

So our main idea is that you can come up with new, emotionally gratifying, motivating, enhancing behaviors that you can do early, then you can best exploit those residual connections because most people off to injury don’t do enough, most people have, not most but 40% of people who buy gym memberships never go.

I had surgery on my shoulder and didn’t even like doing the little bit of Rehab they told me I should do at home. So we need to find ways to really motivate people early to give them large amounts of exercise and practice to sort of exploit these connections you have left. And that’s what we’re really after is how do we do that.

Richard Jacobs: Well, I mean one is the put the fear of God into them and say if you don’t work on this for six months in Rehab it at least three times a week, for instance, then you may have permanent loss of function.

Dr Jon Krakauer: That has been a lot of research over decades showing that that kind of distal warning doesn’t work as well as the thing itself being fun. So you know, lots and lots of people smoke even though they can be told you’re going to get lung cancer and die, they still smoke and the best ways to actually get people to quit smoking is not putting the fear of God in them so much as making it difficult to smoke.

You can’t smoke in restaurants, you can’t smoke in cinemas, and you can’t smoke in public spaces. So in other words, the sheer inconvenience and the expense of buying them seems to be more effective than showing them pictures of black and lungs and things like that.

Similarly, we need to find a way not just to work on fear but to make people actually enjoy doing the rehabilitation so that they want to do it.

Richard Jacobs: So it was your goal to minimize the amount of rehab you have to gamify the experience?

Dr Jon Krakauer: It’s more the second, it’s more to sort of find ways to gain by it and to vary it up and make it immersive so that people actually don’t trick people into doing the intensity and doses that they need that is the approach we’re taking. So, the basic idea is to make the expert athlete of your injury. You know, expert athletes, musician’s practice five, six hours a day and for two reasons, they enjoy the practice and they know that it all helped them be excellent and we need to find people away to make people realize that after injury, essentially you have to become an elite athlete of your injury and we admire athletes so what they do, we mistakenly call it talent or giftedness. But what we’re really impressed by is that they were willing to make the sacrifice to practice five or six hours a day at the expense of everything else. Michael Phelps would practice five or six hours in the pool and he brought death and you’d much rather be out on the town. But he was able to sort of forego those things for the practice and that I think what we need to try and tap into even in patients that alone athletes.

Richard Jacobs: Well that’s a tough hurdle. I mean Rehab of the half-hour a day, I’m sure people don’t want to do. How do you get them to do five, six hours of the equivalent?

Dr Jon Krakauer: I know! Exactly that’s a great question. I mean, how do you get people to do more things? The basic idea is whoever changes behavior wins. I mean, this is true for getting people to lose weight, quit smoking, exercise. It’s the same for Rehab, how do you get people to make the behavioral change? It’s much easier to take a pill or whip out an organ with surgery, but behavioral change over the long term which is probably what’s needed. I mean it’s tough and you know gamification is one way I think.

Richard Jacobs: Well what other ways are you exploring? Like what have you specifically figured out? What have you tried?

Dr Jon Krakauer: Well, we’ve developed games of our own. We are basically trying to get people to play them, we did a little trial after the stroke people like it. In other words, I think what the real issue here is when it comes to the game of vacation is so people were old or sick. They tend to be told to recycle games and devices, which are meant for other people like we use a play station or off the shelf games. And I think what we need to do is we need to sort of accept that we need to deliberately focus on these people and build games for them and that’s what we’re trying to do is what kind of games would you want to develop that are specifically geared towards what we’ve been talking about. And that’s what we did. We basically made people play games where they were dolphins and that was what we started with and people seem to like that they like the idea of being in the ocean. They like the blueness of it all. They like the movement and it seems to be a way of making them make miles of our movements without even realizing they’re doing it.

Richard Jacobs: That’s so good of a, for a joke. The, a, the game of vacation of Thrones, you would adapt the story to that.

Dr Jon Krakauer: Yes! We do want them to be also in stories. That’s absolutely true. We do that and they become characters and they begin to believe they are the characters which is great but the whole idea of making people star in their own rehab is very new, right? I mean how does be part of a story? I always say in my talks, if you’re going to be sick, you might as well enjoy it and people find that weird.

Richard Jacobs: Well can you get together cohorts of people that have had a stroke and had them work together in a multiplayer game?

Dr Jon Krakauer: That’s a really, that is exactly what we’re trying. That’s exactly, that’s a very good idea. Yeah, precisely. I mean they had been stroke groups’ ages where people share their stories and the suffering or what’s happened.

Richard Jacobs: It would actually be cool depending on what happens to someone and what limb is affected, for instance, that’s the character. They become a game and that character have certain abilities, but the character has to be used in such a way that would help them, let’s say it’s a shoulder problem, or a leg problem the character has to act in such a way as to use their abilities and have the rehab themselves.

Dr Jon Krakauer: That’s right and that’s exactly what we do, you are very quick. I mean, that’s exactly what we are doing with isolating particular parts of the body to particular characters and that’s exactly right. You have to do it that way and by doing it with others, it’s competitive. So yes, you’re 100% right. That’s exactly the intuition,

Richard Jacobs: That’s cool that’d be a lot of fun. I could definitely see people doing that competing online, right?

Dr Jon Krakauer: Yes, exactly! But it has to meet the standards that you would want. In other words, as you imagine it in your head right now, it takes about work. In other words, you want it to be high production values and that’s hard because usually, most tech patients are kind of hand me down. No much more interested in making high production value products for teenagers who are well then for elderly people who are sick.

Richard Jacobs: Well I’ll still remember certain games that are popular, they’re popular for a reason, like angry birds, just stepping dud. So you know, reinventing the wheel maybe. Definitely, why that might be better than modify and get licensing, I mean existing things that are super popular and just modifying.

Dr Jon Krakauer: Sure! It’s just that the companies, they go into details of why I don’t think some of these games actually hit the spot with respect to brain us diversity but also many of these companies are very wary of getting into the medical space because suddenly you’d get regulated and so you don’t want to make any claims and if you do make claims, I mean Lumosity was slammed with a big fine when they explained that their games would be helpful for memory loss. So a lot of companies sort of shy away from the medical space. They’re much more interested in the wellness space.

Richard Jacobs: Yeah, you want to avoid claims, but I mean you can still put the modified game out there and just say it’s for use by people in a certain condition. You know, you don’t promise anything or is that not enough to say that?

Dr Jon Krakauer: I think it’s a large investment to sort of modify a game and then have to market it and then get it to that audience. I mean, it’s just not been I feel like you need to sort of doing it from the bottom up and just develop them. But, you know, it’s a mixture. There’ve been data on first-person shooter games having beneficial effects mainly in healthy people but yes you’re intuiting the difficulty of this space. This is not only as of the science difficult and the actual treatment hard, but the model that one should develop in order to do the things we’ve been discussing is itself needs like 10 MBAs.

Richard Jacobs: Well also to the age of the people that have the conditions you’re dealing with they might not want to play first president shooters they’re older they might want to do something else.

Dr Jon Krakauer: That’s right! Exactly right. In other words, you have to be very much aware that they may want more than like nice experiences and even though the average age of people who gain is getting older, I mean, the average age now is in the mid-thirties and many people who have strokes over the age of 65 or never been gamers. So there are lots of challenges and we’ve done our own internal research in terms of what people like and they don’t always want it to be, you know, battle zones.

Richard Jacobs: Yeah! Or what about traditional activities like painting or other things like that?

Dr Jon Krakauer: Yeah, that’s absolutely true. There’s music therapy, there’s art therapy all these things are probably projecting down to a similar overlapping space. The question is how to scale it, how to keep the intensity and dosage up, how to avoid boredom. It’s not every hospital in every country is going to be able to have the artists or the spaces to do that. So one thing is to try and use technology to make it scalable.

Richard Jacobs: Does insurance pay for this or any course?

Dr Jon Krakauer: There’s a big problem right? In other words, if you use technology just as an adjunct to a therapist, therapists have a designated amount of time available and so no amount of technology is going to be able to make up the fatter. The therapist cannot spend enough time with the patients. So you know, either you find ways to not require therapists there. They do things at home, for example, you have to change the reimbursement structure. Some countries are more flexible than others. The United States particularly inflexible because it’s really economic considerations that drive rehab rather than scientific ones.

So it’s a real uphill struggle. You can even say you’ve got evidence and it’s still difficult. I mean people say that it takes on average about 17 years to get from a piece of good evidence to changing medical practice so it’s an uphill struggle no matter how good your data are.

Richard Jacobs: Well maybe the key is informing communities what we will have like afflictions and equally in the gamification within the community, literally membership in a community

Dr Jon Krakauer: Yeah! I mean I think that’s really interesting. I mean, sometimes we think about that sort of Uber rising it right? In other words, instead of sort of saying it has to go all the way through as you make it minimum risk enough and then people just begin to ask for it in their communities and you sort of short circuit the entire reimbursement system, they all bet boils down to whether people want to pay for things out of pocket. Even if they’re reasonable compared to going through their insurance and their insurance only covers the piece, they may say, well that might be good enough or they’re going to chop it up themselves. There’s a lot of work suggesting that if people think they get even a piece of treatment through their insurance, they’d rather just do that and not pay extra. It’s fascinating.

Richard Jacobs: Well there’s gotta be a reason that you’re doing this and in a way to do it. I mean you can say like you’re in a thankless position, so why do it, you know?

Dr Jon Krakauer: Oh yeah. I think that worldwide, I’m optimistic. I agree with you. I think that worldwide there are lots of different ways. One can do it, there are lots of avenues to pursue. Overall. I think if you are what you’re doing is right and people like it and helps people eventually in some venues in some way, it goes and that’s what I have to believe. Otherwise. You’re right! I would just be soaked in pessimism.

Richard Jacobs: Well, how far have you gotten any good results with a cohort of people?

Dr Jon Krakauer: Sure. I mean we’ve got a small trial with the dolphin in the acute stroke patients and we got positive results, which we’re writing up right now. We’ve run about a dozen patients in an assisted living facility to see whether it’s tolerable and enjoyable for the healthy elderly. We’re beginning to look at other patient populations with it. So yes I think we’re on the right track.

Richard Jacobs: Okay! Very good! So what’s coming for you in the next year or so? Any projects or whether they add on to working on?

Dr Jon Krakauer: Yeah! We’re building new tech we’re going to roll out a sort of 2.0 version of our creatures. We’re going to do something for the hand and we’re going to expand the conditions with their lookout with no trial, do some small phase two studies in TBI multiple sclerosis HIV and then try and do bigger trials in stroke and chronic and acute stroke so it’s really perfect. The platform increases the number of characters and experiences and the other thing we’re working on which is very exciting is we’re trying to sort of build the hospital room of the future. In other words, not just have platforms but sort of turn rooms more into like little spaceships that you can walk into a sort of inspired by the sort of the Holodeck in Star Trek wouldn’t it be great if instead of a hospital room it felt more like an arcade.

That’s the kind of thing we’re also working on here at Hopkins.

Richard Jacobs: Well it seems like this would lend itself to VR. Yeah, that would be a huge way to do this. You know, I give you let’s say I have my shoulder and I remember the exercises I did. You know, if I’m in VR, I could have a virtual trainer that tells me to do this, do that, try to move your shoulder this way. I could even show an image of myself doing the movements as I’m doing it and you show the muscles are like a cutaway. I mean there can be a lot of things with VR.

Dr Jon Krakauer: Yeah we have a VR version of our game. So yeah, I mean VR is one potential way. I mean, the thing about VR is sometimes you have to see why that’s better than reality itself sometimes I feel too many VR experiences just replicas of reality and it’s a very interesting distinction and a very interesting conversation to have.

What is the difference between VR versus gaming and VR hasn’t really taken off yet as something that people like to have as a gaming experience but I think it’s in early days and that will probably change.

Richard Jacobs: Okay! Well very good. So what’s the best way for folks to find out more and to get in touch?

Dr Jon Krakauer: Well, the best way I think is to go to our website, so it’s www.Blam-lab.org, and we have contact information and all our media and our scientific manuscripts work that we’ve done and then there’s also you can go to Hopkins and go to the Kata Design Studio and that will also give information about the kind of games I make.

Richard Jacobs: Ok Right! Great. And BLAM is BLAM-LAB.ORG. Okay! Very good. Thanks for coming. I really appreciate it.

Dr Jon Krakauer: Thank you so much for having me. It was great fun.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download | Embed

In this conversation, we sit down with a member of Doomberg to discuss the mindset of continuous improvement and other thought-provoking ideas that are important for us all… Read More

In this episode, we discuss teenage social anxiety with Kyle Mitchell, a Tedx Speaker, author, and the founder of Social Anxiety Kyle. With a passion for solving mental… Read More

In this episode, we are joined by Matthew Moody, the President of Mental Health America of Arizona and a licensed counselor in Arizona. He has a Bachelor’s degree… Read More

Do pre and probiotics have healing and preventive powers? In an age of pharmaceutical solutions, finding sustainable and holistic health practices is critical. How can we leverage gut… Read More

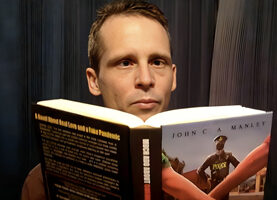

John C. A. Manley joins the podcast once again to discuss his daily email newsletter, Blazing Pine Cone Posts, and his work as a writer of fiction, freedom,… Read More

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get The Latest Finding Genius Podcast News Delivered To Your Inbox